Courtesy of Legal Services of New Jersey

[ipaper docId=46466367 access_key=key-448g7r9wonwz1j4ufuq height=600 width=600 /]

© 2010-19 FORECLOSURE FRAUD | by DinSFLA. All rights reserved.

Posted on 07 January 2011.

Courtesy of Legal Services of New Jersey

[ipaper docId=46466367 access_key=key-448g7r9wonwz1j4ufuq height=600 width=600 /]

© 2010-19 FORECLOSURE FRAUD | by DinSFLA. All rights reserved.Posted in STOP FORECLOSURE FRAUD0 Comments

![[NYSC] JUDGE SCHACK TAKES ON ROBO-SIGNER ERICA JOHNSON SECK: ONEWEST BANK v. DRAYTON (3)](https://stopforeclosurefraud.com/wp-content/themes/gazette/thumb.php?src=wp-content/uploads/2010/10/2strikes.jpg&w=100&h=57&zc=1&q=90)

Posted on 30 October 2010.

.

15183/09.Supreme Court, Kings County.

Decided October 21, 2010.Gerald Roth, Esq., Stein Wiener and Roth, LLP, Carle Place NY, Defendant did not answer Plaintiff.

ARTHUR M. SCHACK, J.

In this foreclosure action, plaintiff ONEWEST BANK, F.S.B. (ONEWEST), moved for an order of reference and related relief for the premises located at 962 Hemlock Street, Brooklyn, New York (Block 4529, Lot 116, County of Kings), upon the default of all defendants. The Kings County Supreme Court Foreclosure Department forwarded the motion papers to me on August 30, 2010. While drafting this decision and order, I received on October 14, 2010, in the midst of the present national media attention about “robo-signers,” an October 13, 2010-letter from plaintiff’s counsel, by which “[i]t is respectfully requested that plaintiff’s application be withdrawn at this time.” There was no explanation or reason given by plaintiff’s counsel for his request to withdraw the motion for an order of reference other than “[i]t is our intention that a new application containing updated information will be re-submitted shortly.”

The Court grants the request of plaintiff’s counsel to withdraw the instant motion for an order of reference. However, to prevent the waste of judicial resources, the instant foreclosure action is dismissed without prejudice, with leave to renew the instant motion for an order of reference within sixty (60) days of this decision and order, by providing the Court with necessary and additional documentation.

First, the Court requires proof of the grant of authority from the original mortgagee, CAMBRIDGE HOME CAPITAL, LLC (CAMBRIDGE), to its nominee, MORTGAGE ELECTRONIC REGISTRATION SYSTEMS, INC. (MERS), to assign the subject mortgage and note on March 16, 2009 to INDYMAC FEDERAL BANK, FSB (INDYMAC). INDYMAC subsequently assigned the subject mortgage and note to its successor, ONEWEST, on May 14, 2009.

Second, the Court requires an affidavit from Erica A. Johnson-Seck, a conflicted “robo-signer,” explaining her employment status. A “robo-signer” is a person who quickly signs hundreds or thousands of foreclosure documents in a month, despite swearing that he or she has personally reviewed the mortgage documents and has not done so. Ms. Johnson-Seck, in a July 9, 2010 deposition taken in a Palm Beach County, Florida foreclosure case, admitted that she: is a “robo-signer” who executes about 750 mortgage documents a week, without a notary public present; does not spend more than 30 seconds signing each document; does not read the documents before signing them; and, did not provide me with affidavits about her employment in two prior cases. (See Stephanie Armour, “Mistakes Widespread on Foreclosures, Lawyers Say,” USA Today, Sept. 27, 2010; Ariana Eunjung Cha, “OneWest Bank Employee: Not More Than 30 Seconds’ to Sign Each Foreclosure Document,” Washington Post, Sept. 30, 2010).

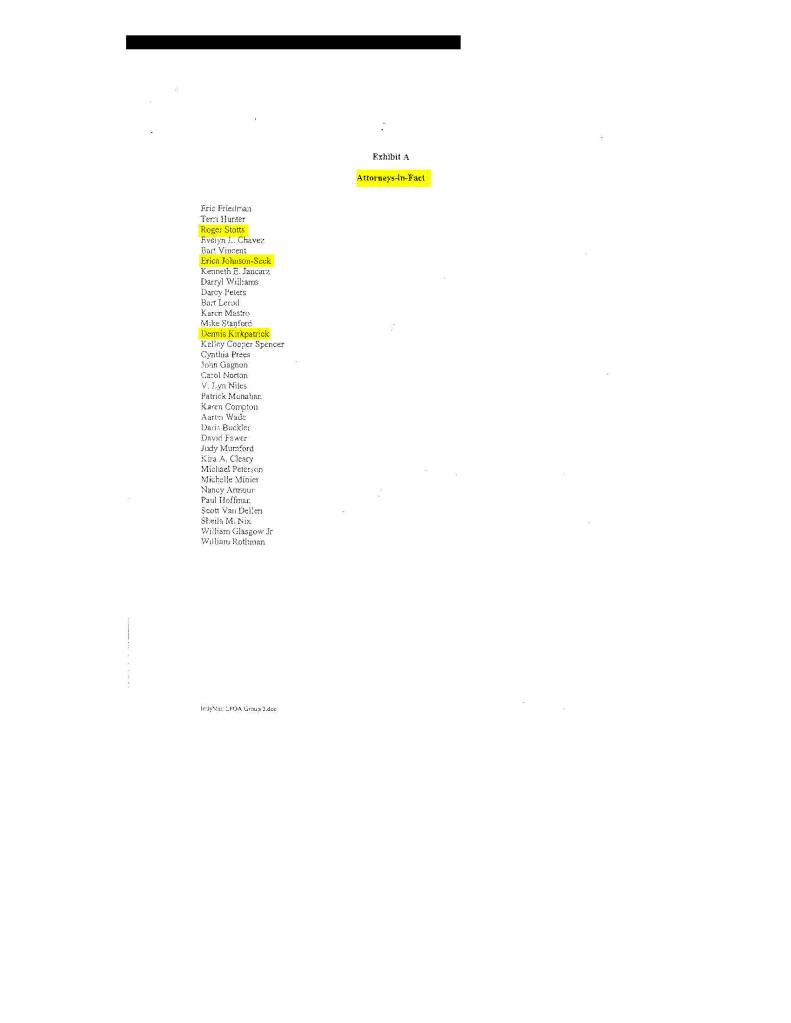

In the instant action, Ms. Johnson-Seck claims to be: a Vice President of MERS in the March 16, 2009 MERS to INDYMAC assignment; a Vice President of INDYMAC in the May 14, 2009 INDYMAC to ONEWEST assignment; and, a Vice President of ONEWEST in her June 30, 2009-affidavit of merit. Ms. Johnson-Seck must explain to the Court, in her affidavit: her employment history for the past three years; and, why a conflict of interest does not exist in the instant action with her acting as a Vice President of assignor MERS, a Vice President of assignee/assignor INDYMAC, and a Vice President of assignee/plaintiff ONEWEST. Further, Ms. Johnson-Seck must explain: why she was a Vice President of both assignor MERS and assignee DEUTSCHE BANK in a second case before me, Deutsche Bank v Maraj, 18 Misc 3d 1123 (A) (Sup Ct, Kings County 2008); why she was a Vice President of both assignor MERS and assignee INDYMAC in a third case before me, Indymac Bank, FSB, v Bethley, 22 Misc 3d 1119 (A) (Sup Ct, Kings County 2009); and, why she executed an affidavit of merit as a Vice President of DEUTSCHE BANK in a fourth case before me, Deutsche Bank v Harris (Sup Ct, Kings County, Feb. 5, 2008, Index No. 35549/07).

Third, plaintiff’s counsel must comply with the new Court filing requirement, announced yesterday by Chief Judge Jonathan Lippman, which was promulgated to preserve the integrity of the foreclosure process. Plaintiff’s counsel must submit an affirmation, using the new standard Court form, that he has personally reviewed plaintiff’s documents and records in the instant action and has confirmed the factual accuracy of the court filings and the notarizations in these documents. Counsel is reminded that the new standard Court affirmation form states that “[t]he wrongful filing and prosecution of foreclosure proceedings which are discovered to suffer from these defects may be cause for disciplinary and other sanctions upon participating counsel.”

Defendant COVAN DRAYTON (DRAYTON) executed the subject

mortgage and note on January 12, 2007, borrowing $492,000.00 from CAMBRIDGE. MERS “acting solely as a nominee for Lender [CAMBRIDGE]” and “FOR PURPOSES OF RECORDING THIS MORTGAGE, MERS IS THE MORTGAGEE OF RECORD,” recorded the instant mortgage and note on March 19, 2007, in the Office of the City Register of the City of New York, at City Register File Number (CRFN) XXXXXXXXXXXXX. Plaintiff DRAYTON allegedly defaulted in his mortgage loan payment on September 1, 2008. Then, MERS, as nominee for CAMBRIDGE, assigned the instant nonperforming mortgage and note to INDYMAC, on March 16, 2009. Erica A. Johnson-Seck executed the assignment as a Vice President of MERS, as nominee for CAMBRIDGE. This assignment was recorded in the Office of the City Register of the City of New York, on March 24, 2009, at CRFN XXXXXXXXXXXX. However, as will be discussed below, there is an issue whether MERS, as CAMBRIDGE’s nominee, was authorized by CAMBRIDGE, its principal, to assign the subject DRAYTON mortgage and note to plaintiff INDYMAC. Subsequently, almost two months later, Ms. Johnson-Seck, now as a Vice President of INDYMAC, on May 14, 2009, assigned the subject mortgage and note to ONEWEST. This assignment was recorded in the Office of the City Register of the City of New York, on May 22, 2009, at CRFN XXXXXXXXXXXXX. Plaintiff ONEWEST commenced the instant foreclosure action on June 18, 2009 with the filing of the summons, complaint and notice of pendency. On August 6, 2009, plaintiff ONEWEST filed the instant motion for an order of reference. Attached to plaintiff ONEWEST’s moving papers is an affidavit of merit by Erica A. Johnson-Seck, dated June 30, 2009, in which she claims to be a Vice President of plaintiff ONEWEST. She states, in ¶ 1, that “[t]he facts recited herein are from my own knowledge and from review of the documents and records kept in the ordinary course of business with respect to the servicing of this mortgage.” There are outstanding questions about Ms. Johnson-Seck’s employment, whether she executed sworn documents without a notary public present and whether she actually read and personally reviewed the information in the documents that she executed.

On July 9, 2010, nine days after executing the affidavit of merit in the instant action, Ms. Johnson-Seck was deposed in a Florida foreclosure action, Indymac Federal Bank, FSB, v Machado (Fifteenth Circuit Court in and for Palm Beach County, Florida, Case No. 50 2008 CA 037322XXXX MB AW), by defendant Machado’s counsel, Thomas E. Ice, Esq. Ms. Johnson-Seck admitted to being a “robo-signer,” executing sworn documents outside the presence of a notary public, not reading the documents before signing them and not complying with my prior orders in the Maraj and Bethley decisions. Ms. Johnson-Seck admitted in her Machado deposition testimony that she was not employed by INDYMAC on May 14, 2009, the day she assigned the subject mortgage and note to ONEWEST, even though she stated in the May 14, 2009 assignment that she was a Vice President of INDYMAC. According to her testimony she was employed on May 14, 2010 by assignee ONEWEST. The following questions were asked and then answered by Ms. Johnson Seck, at p. 4, line 11-p. 5, line 4:

Q. Could you state your full name for the record, please.

A. Erica Antoinette Johnson-Seck.

Q. And what is your business address?

A. 7700 West Parmer Lane, P-A-R-M-E-R, Building D, Austin, Texas 78729.

Q. And who is your employer?

A. OneWest Bank.

Q. How long have you been employed by OneWest Bank?

A. Since March 19th, 2009.

Q. Prior to that you were employed by IndyMac Federal Bank, FSB?

A. Yes.

Q. And prior to that you were employed by IndyMac Bank, FSB?

A. Yes.

Q. Your title with OneWest Bank is what?

A. Vice president, bankruptcy and foreclosure.

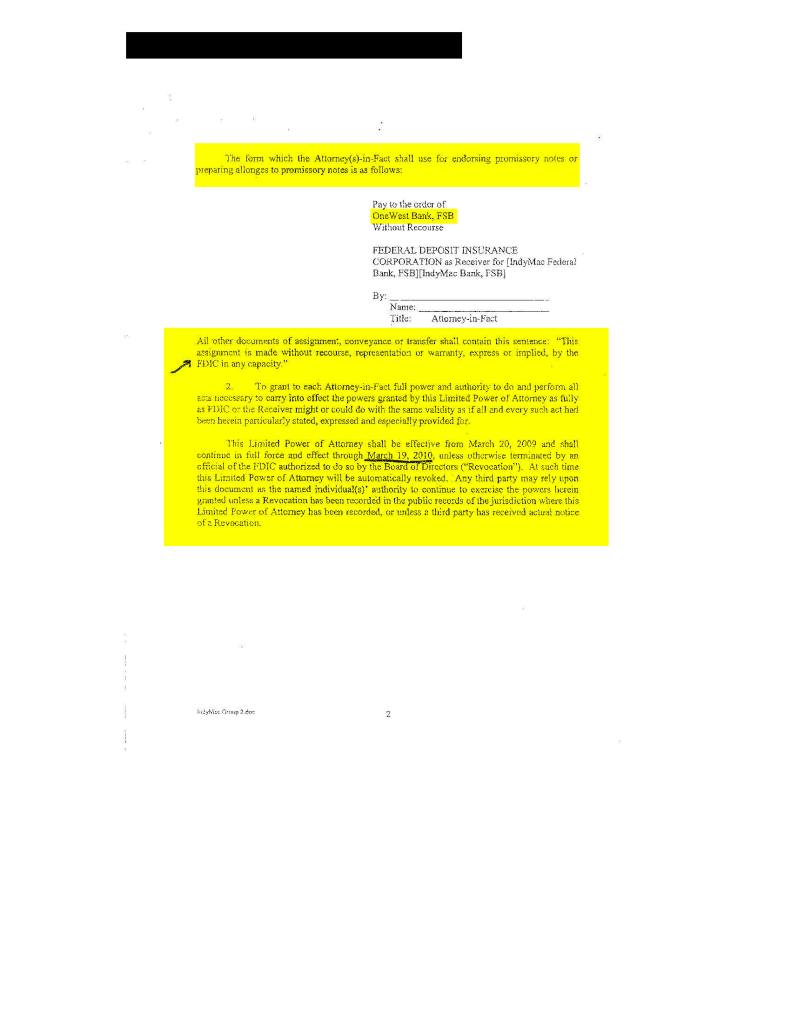

Despite executing, on March 16, 2009, the MERS, as nominee for CAMBRIDGE, assignment to INDYMAC, as Vice President of MERS, she admitted that she is not an officer of MERS. Further, she claimed to have “signing authority” from several major banking institutions and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). The following questions were asked and then answered by Ms. Johnson-Seck, at p. 6, lines 5-21:

Q. Are you also an officer of Mortgage Electronic Registration Systems?

A. No.

Q. You have signing authority to sign on behalf of Mortgage Electronic Registration Systems as a vice president, correct?

A. Yes.

Q. Are you an officer of any other corporation?

A. No.

Q. Do you have signing authority for any other corporation?

A. Yes.

Q. What corporations are those?

A. IndyMac Federal Bank, Indymac Bank, FSB, FDIC as receiver for Indymac Bank, FDIC as conservator for Indymac, Deutsche Bank, Bank of New York, U.S. Bank. And that’s all I can think of off the top of my head.

Then, she answered the following question about her “signing authority,” at page 7, lines 3-10:

Q. When you say you have signing authority, is your authority to sign as an officer of those corporations?

A. Some.

Deutsche Bank I have a POA [power of attorney] to sign as attorney-in-fact. Others I sign as an officer. The FDIC I sign as attorney-in-fact. IndyMac Bank and IndyMac Federal Bank I now sign as attorney-in-fact. I only sign as a vice president for OneWest. Ms. Johnson-Seck admitted that she is not an officer of MERS, has no idea how MERS is organized and does not know why she signs assignments as a MERS officer. Further, she admitted that the MERS assignments she executes are prepared by an outside vendor, Lender Processing Services, Inc. (LPS), which ships the documents to her Austin, Texas office from Minnesota. Moreover, she admitted executing MERS assignments without a notary public present. She also testified that after the MERS assignments are notarized they are shipped back to LPS in Minnesota. LPS, in its 2009 Form 10-K, filed with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, states that it is “a provider of integrated technology and services to the mortgage lending industry, with market leading positions in mortgage processing and default management services in the U.S. [p. 1]”; “we offer lenders, servicers and attorneys certain administrative and support services in connection with managing foreclosures [p. 4]”; “[a] significant focus of our marketing efforts is on the top 50 U.S. banks [p. 5]”; and, “our two largest customers, Wells Fargo Bank, N.A. and JP Morgan Chase Bank, N.A., each accounted for more than 10% of our aggregate revenue [p. 5].”LPS is now the subject of a federal criminal investigation related to its foreclosure document preparation. (See Ariana Eunjung Cha. “Lender Processing Services Acknowledges Employees Allowed to Sign for Managers on Foreclosure Paperwork,” Washington Post, Oct. 5, 2010). Last week, on October 13, 2010, the Florida Attorney-General issued to LPS an “Economic Crimes Investigative Subpoena Duces Tecum,” seeking various foreclosure documents prepared by LPS and employment records for various “robo-signers.” The following answers to questions were given by Ms. Johnson-Seck in the Machado deposition, at p. 116, line 4-p. 119, line 16:

Q. Now, given our last exchange, I’m sure you will agree that you are not a vice president of MERS in any sense of the word other than being authorized to sign as one?

A. Yes.

Q. You are not —

A. Sorry.

Q. That’s all right. You are not paid by MERS?

A. No.

Q. You have no job duties as vice president of MERS?

A. No.

Q. You don’t attend any board meetings of MERS?

A. No.

Q. You don’t attend any meetings at all of MERS?

A. No.

Q. You don’t report to the president of MERS?

A. No.

Q. Who is the president of MERS?

A. I have no idea.

Q. You’re not involved in any governance of MERS?

A. No.

Q. The authority you have says that you can be an assistant secretary, right?

A. Yes.

Q. And yet you don’t report to the secretary —

A. No.

Q. — of MERS. You don’t have any MERS’ employees who report to you?

A. No.

Q. You don’t have any vote or say in any corporate decisions of MERS?

A. No.

Q. Do you know where the MERS’ offices are located?

A. No.

Q. Do you know how many offices they have?

A. No.

Q. Do you know where they are headquartered?

A. No.

Q. I take it then you’re never been to their headquarters?

A. No.

Q. Do you know how many employees they have?

A. No.

Q. But you know that you have counterparts all over the country signing as MERS’s vice-presidents and assistant secretaries?

A. Yes.

Q. Some of them are employees of third-party foreclosure service companies, like LPS?

A. Yes.

Q. Why does MERS appoint you as a vice president or assistant secretary as opposed to a manager or an authorized agent to sign in that capacity?

A. I don’t know.

Q. Why does MERS give you any kind of a title?

A. I don’t know.

Q. Take me through the procedure for drafting and — the drafting and execution of this Assignment of Mortgage which is Exhibit E.

A. It is drafted by our forms, uploaded into process management, downloaded by LPS staff in Minnesota, shipped to Austin where we sign and notarize it, and hand it back to an LPS employee, who then ships it back to Minnesota, up uploads a copy and mails the original to the firm.

Q. Very similar to all the other document, preparation of all the other documents.

A. (Nods head.)

Q. Was that a yes? You were shaking your head.

A. Yes.

Q. As with the other documents, you personally don’t review any of the information that’s on here —

A. No.

Q. — other than to make sure that you are authorized to sign as the person you’re signing for?

A. Yes.

Q. Okay. As with the other documents, you signed these and took them to be notarized just to a Notary that’s outside your office?

A. Yes.

Q. And they will get notarized as soon as they can. It may or may not be the same day that you executed it?

A. That’s true. Further, with respect to MERS, Ms. Johnson-Seck testified in answering questions, at p. 138, line 2-p. 139, line 17:

Q. Do you have an understanding that MERS is a membership organization?

A. Yes, yes.

Q. And the members are —

A. Yes.

Q. — banking entities such as OneWest?

A. Yes.

Q. In fact, OneWest is a member of MERS?

A. Yes.

Q. Is Deutsche Bank National Trust Company a member of MERS?

A. I don’t know.

Q. Most of the major banking institutions in the Untied States, at least, are members of MERS, correct?

A. That sounds right.

Q. It’s owned and operated by banking institutions?

A. I’m not a big — I don’t, I don’t know that much about the ins and outs of MERS. I’m sorry. I understand what it’s for, but I don’t understand the nitty-gritty.

Q. What is it for?

A. To track the transfer of doc — of interest from one entity to another. I know that it was initially created so that a servicer did not have to record the assignments, or if they didn’t, there was still a system to keep track of the transfer of property.

Q. Does it also have a function to hold the mortgage separate and apart from the note so that note can be transferred from entity to entity to entity, bank to bank to bank —

A. That sounds right.

Q. — without ever having to rerecord the mortgage?

A. That sounds right.

Q. So it’s a savings device. It makes it more efficient to transfer notes?

A. Yes.

Q. And cheaper?

A. Yes. Moreover,

Ms. Johnson-Seck testified that one of her job duties was to sign documents, which at that time took her about ten minutes per day [p. 11]. Further, she admitted, at p. 13, line 11-p. 14, line 15, that she signs about 750 documents per week and doesn’t read each document.

Q. Okay. How many documents would you say that you sign on a week on average, in a week on average?

A. I could have given you that number if you had that question in there because I would brought the report. However, I’m going to guess, today I saw an e-mail that 1,073 docs are in the office for signing. So if we just — and there’s about that a day. So let’s say 6,000 a week and I do probably — let’s see. There’s eight of us signing documents, so what’s the math?

Q. Six thousand divided by eight, that gives me 750..

A. That sounds, that sounds about right.

Q. Okay. That would be a reasonable estimate of how many you sign, you personally sign per week?

A. Yes.

Q. And that would include Lost Note Affidavits, Affidavits of Debt?

A. Yes.

Q. What other kinds of documents would be included in that?

A. Assignments, declarations. I can sign anything related to a bankruptcy or a foreclosure.

Q. How long do you spend executing each document?

A. I have changed my signature considerably. It’s just an E now.

So not more than 30 seconds.

Q. Is it true that you don’t read each document before you sign it?

A. That’s true. [Emphasis added]

Ms. Johnson-Seck, in the instant action, signed her full name on the March 16, 2009 MERS, as nominee for CAMBRIDGE, assignment to INDYMAC. She switched to the letter E in signing the May 14, 2009 INDYMAC to ONEWEST assignment and the June 30, 2009 affidavit of merit on behalf of ONEWEST. Additionally. she testified about how LPS prepares the documents in Minnesota and ships them to her Austin office, with LPS personnel present in her Austin office [pp. 16-17]. Ms. Johnson-Seck described the document signing process, at p. 17, line 6-p. 18, line 18:

Q. Take me through the procedure for getting your actual signature on the documents once they’ve gone through this quality control process?

A. The documents are delivered to me for signature and I do a quick purview to make sure that I’m not signing for an entity that I cannot sign for. And I sign the document and I hand it to the Notary, who notarizes it, who then hands it back to LPS who uploads the document so that the firms know it’s available and they send an original.

Q. “They” being LPS?

A. Yes.

Q. Are all the documents physically, that you were supposed to sign, are they physically on your desk?

A. Yes.

Q. You don’t go somewhere else to sign documents?

A. No.

Q. When you sign them, there’s no one else in your office?

A. Sometimes.

Q. Well, the Notaries are not in your office, correct?

A. They don’t sit in my office, no.

Q. And the witnesses who, if you need witnesses on the document, are not sitting in your office?

A. That’s right.

Q. So you take your ten minutes and you sign them and then you give them to the supervisor of the Notaries, correct?

A. I supervise the Notaries, so I just give them to a Notary.

Q. You give all, you give the whole group that you just signed to one Notary?

A. Yes. [Emphasis added]

Ms. Johnson-Seck testified, at p. 20, line 1-p. 21, line 4 about notaries not witnessing her signature:

Q. I’m mostly interested in how long it takes for the Notary to notarize your signature.

A. I can’t say categorically because the Notary, that’s not the only job they do, so.

Q. In any event, it doesn’t have to be the same day?

A. No.

Q. When they notarize it and they put a date that they’re notarizing it, is it the date that you signed it or is it the date that they’re notarizing it?

A. I don’t know.

Q. When you execute a sworn document, do you make any kind of a verbal acknowledgment or oath to anyone?

A. I don’t know if I know what you’re talking about. What’s a sworn document?

Q. Well, an affidavit.

A. Oh. No.

Q. In any event, there’s no Notary in the room for you to —

A. Right.

Q. — take an oath with you, correct?

A. No there is not.

Q. In fact, the Notaries can’t see you sign the documents; is that correct?

A. Not unless that made it their business to do so?

Q. To peek into your office?

A. Yes. [Emphasis added]

As noted above, I found Ms. Johnson-Seck engaged in “robo-signing” in Deutsche Bank v Maraj and Indymac Bank, FSB, v Bethley. In both foreclosure cases I denied plaintiffs’ motions for orders of reference without prejudice with leave to renew if, among other things, Ms. Johnson-Seck could explain in affidavits: her employment history for the past three years; why she was a Vice President of both assignor MERS and assignee Deutsche Bank National Trust Company in Maraj; and, Vice President of INDYMAC in Bethley. Mr. Ice questioned Ms. Johnson-Seck about my MarajMaraj decision as exhibit M in the Machado deposition. The following colloquy at the Maraj deposition took place at p. 153, line 15-p. 156, line 9. decision and showed her the

Q. Exhibit M is a document that you saw before in your last deposition, correct?

A. Yes.

Q. It’s an opinion from Judge Schack up in New York —

A. Yes.

Q. — correct? You’re familiar with that?

A. Yes.

Q. In it, he says that you signed an Assignment of Mortgage as the vice president of MERS, correct —

A. Yes.

Q. — just as you did in this case? Judge Schack also says that you executed an affidavit as an officer of Deutsche Bank National Trust Company, correct?

A. Yes.

Q. And is that true, you executed an affidavit for Deutsche Bank in that case?

A. That is not true.

Q. You never executed a document as an officer of Deutsche Bank National Trust Company in that case, Judge Schack’s case?

A. Let me just read it so I can — I have to refresh my memory completely.

Q. Okay.

A. I don’t remember. Most likely.

Q. That you did?

A. It sounds reasonable that I may have. I don’t remember, and since it’s not attached, I can’t say.

Q. And as a result, Judge Schack wanted to know if you were engaged in self-dealing by wearing two corporate hats?

A. Yes.

Q. And the court was concerned that there may be fraud on the part of the bank?

A. I guess.

Q. I mean he said that, right?

A. Oh, okay. I didn’t read the whole thing. Okay.

Q. Okay. The court ordered Deutsche Bank to produce an affidavit from you describing your employment history for the past three years, correct?

A. That’s what this says.

Q. Did you do that?

A. No, because we were never — no affidavit ever existed and no request ever came to produce such a document. The last time we spoke, I told you that in-house counsel was reviewing the whole issue and that’s kind of where — and we still haven’t received any communication to produce an affidavit.

Q. From your counsel?

A. From anywhere.

Q. Well, you’re reading Judge Schack’s opinion. He seems to want one. Isn’t that pretty clear on its face.

A. We didn’t get — we never even got a copy of this.

Q. Okay. But now you have it —

A. And —

Q. And you had it when we met at our deposition back in February 5th.

A. And our in-house counsel’s response to this is we were never — this was never requested of me and it was his recommendation not to comply.

Q. What has become of that case?

A. I don’t know.

Q. Was it settled?

A. I don’t know. After a break in the Machado deposition proceedings, Mr. Ice questioned Ms. Johnson-Seck about various documents that were subpoenaed for the July 9, 2010 deposition, including her employment affidavits that I required in both Maraj and Bethley. Ms. Johnson-Seck answered the following questions at p. 159, line 19-p. 161, line 9:

Q. So let’s start with the duces tecum part of you notice, which is the list of documents. No. 1 was: The affidavit of the last three years of deponent’s employment provided to Judge Schack in response to the order dated January 31st, 2008 in the case of Deutsche Bank National Trust Company vs. Maraj, Case No. 25981-07, Supreme Court of New York. We talked about that earlier. There is no such affidavit, correct?

A. Correct.

Q. By the way, why was IndyMac permitted to bring the case in Deutsche Bank’s name in that case?

A. I don’t — I don’t know. Now, errors have been made.

Q. No. 2: The affidavit of the deponent provided to Judge Schack in response to the order dated February 6th, 2009 in the case of IndyMac Bank, FSB vs, Bethley, New York Slip Opinion 50186, New York Supreme Court 2/5/09, “explaining,” and this is in quotes, “her employment history for the past three years; and, why a conflict of interest does not exist in how she acted as vice president of assignee IndyMac Bank, FSB in the instant action, and vice president of both Mortgage Electronic Registrations Systems, Inc. and Deutsche Bank in Deutsche Bank vs. Maraj,” and it gives the citation and that’s the case referred to in item 1 of our request. Do you have that affidavit with you here today?

A. No.

Q. Were you aware of that second opinion where Judge Schack asks for a second affidavit?

A. Nope. Where is Judge Schack sending these?

Q. Presumably to your counsel.

A. I wonder if he has the right address. Maybe that’s what we should do, send Judge Schack the most recent, and I will gladly show up in his court and provide him everything he wants.

Q. Okay. Well, I sent you this back in March. Have your or your counsel or in-house counsel at IndyMac pursued that?

A. No. [Emphasis added] Counsel for plaintiff ONEWEST has leave to produce Ms. Johnson-Seck in my courtroom to “gladly show up . . . and provide [me] . . . everything he wants.”

Real Property Actions and Proceedings Law (RPAPL) § 1321 allows the Court in a foreclosure action, upon the default of the defendant or defendant’s admission of mortgage payment arrears, to appoint a referee “to compute the amount due to the plaintiff.” In the instant action, plaintiff ONEWEST’s application for an order of reference is a preliminary step to obtaining a default judgment of foreclosure and sale against defendant DRAYTON. (Home Sav. of Am., F.A. v Gkanios, 230 AD2d 770 [2d Dept 1996]). Plaintiff’s request to withdraw its application for an order of reference is granted. However, to allow this action to continue without seeking the ultimate purpose of a foreclosure action, to obtain a judgment of foreclosure and sale, makes a mockery of and wastes the resources of the judicial system. Continuing the instant action without moving for an order of reference is the judicial equivalent of a “timeout.” Granting a “timeout” to plaintiff ONEWEST to allow it to re-submit “a new application containing new information . . . shortly” is a waste of judicial resources. Therefore, the instant action is dismissed without prejudice, with leave granted to plaintiff ONEWEST to renew its motion for an order of reference within sixty (60) days of this decision and order, if plaintiff ONEWEST and plaintiff ONEWEST’s counsel can satisfactorily address the various issues previously enumerated. Further, the dismissal of the instant foreclosure action requires the cancellation of the notice of pendency. CPLR § 6501 provides that the filing of a notice of pendency against a property is to give constructive notice to any purchaser of real property or encumbrancer against real property of an action that “would affect the title to, or the possession, use or enjoyment of real property, except in a summary proceeding brought to recover the possession of real property.” The Court of Appeals, in 5308 Realty Corp. v O & Y Equity Corp. (64 NY2d 313, 319 [1984]), commented that “[t]he purpose of the doctrine was to assure that a court retained its ability to effect justice by preserving its power over the property, regardless of whether a purchaser had any notice of the pending suit,” and, at 320, that “the statutory scheme permits a party to effectively retard the alienability of real property without any prior judicial review.” CPLR § 6514 (a) provides for the mandatory cancellation of a notice of pendency by:

The Court, upon motion of any person aggrieved and upon such notice as it may require, shall direct any county clerk to cancel a notice of pendency, if service of a summons has not been completed within the time limited by section 6512; or if the action has been settled, discontinued or abated; or if the time to appeal from a final judgment against the plaintiff has expired; or if enforcement of a final judgment against the plaintiff has not been stayed pursuant to section 551. [emphasis added] The plain meaning of the word “abated,” as used in CPLR § 6514 (a) is the ending of an action. “Abatement” is defined as “the act of eliminating or nullifying.” (Black’s Law Dictionary 3 [7th ed 1999]). “An action which has been abated is dead, and any further enforcement of the cause of action requires the bringing of a new action, provided that a cause of action remains (2A Carmody-Wait 2d § 11.1).” (Nastasi v Nastasi, 26 AD3d 32, 40 [2d Dept 2005]). Further, Nastasi at 36, held that the “[c]ancellation of a notice of pendency can be granted in the exercise of the inherent power of the court where its filing fails to comply with CPLR § 6501 (see 5303 Realty Corp. v O & Y Equity Corp., supra at 320-321; Rose v Montt Assets, 250 AD2d 451, 451-452 [1d Dept 1998]; Siegel, NY Prac § 336 [4th ed]).” Thus, the dismissal of the instant complaint must result in the mandatory cancellation of plaintiff ONEWEST’s notice of pendency against the subject property “in the exercise of the inherent power of the court.”

Moreover, “[t]o have a proper assignment of a mortgage by an authorized agent, a power of attorney is necessary to demonstrate how the agent is vested with the authority to assign the mortgage.” (HSBC Bank, USA v Yeasmin, 27 Misc 3d 1227 [A], *3 [Sup Ct, Kings County 2010]). “No special form or language is necessary to effect an assignment as long as the language shows the intention of the owner of a right to transfer it [Emphasis added].” (Tawil v Finkelstein Bruckman Wohl Most & Rothman, 223 AD2d 52, 55 [1d Dept 1996]). (See Suraleb, Inc. v International Trade Club, Inc., 13 AD3d 612 [2d Dept 2004]). MERS, as described above, recorded the subject mortgage as “nominee” for CAMBRIDGE. The word “nominee” is defined as “[a] person designated to act in place of another, usu. in a very limited way” or “[a] party who holds bare legal title for the benefit of others.” (Black’s Law Dictionary 1076 [8th ed 2004]). “This definition suggests that a nominee possesses few or no legally enforceable rights beyond those of a principal whom the nominee serves.” (Landmark National Bank v Kesler, 289 Kan 528, 538 [2009]). The Supreme Court of Kansas, in Landmark National Bank, 289 Kan at 539, observed that: The legal status of a nominee, then, depends on the context of the relationship of the nominee to its principal. Various courts have interpreted the relationship of MERS and the lender as an agency relationship. See In re Sheridan, 2009 WL631355, at *4 (Bankr. D. Idaho, March 12, 2009) (MERS “acts not on its own account. Its capacity is representative.”); Mortgage Elec. Registrations Systems, Inc. v Southwest,La Salle Nat. Bank v Lamy, 12 Misc 3d 1191 [A], at *2 [Sup Ct, Suffolk County 2006]) . . . (“A nominee of the owner of a note and mortgage may not effectively assign the note and mortgage to another for want of an ownership interest in said note and mortgage by the nominee.”) The New York Court of Appeals in MERSCORP, Inc. v Romaine (8 NY3d 90 [2006]), explained how MERS acts as the agent of mortgagees, holding at 96: In 1993, the MERS system was created by several large participants in the real estate mortgage industry to track ownership interests in residential mortgages. Mortgage lenders and other entities, known as MERS members, subscribe to the MERS system and pay annual fees for the electronic processing and tracking of ownership and transfers of mortgages. Members contractually agree to appoint MERS to act as their common agent on all mortgages they register in the MERS system. [Emphasis added] 2009 Ark. 152 ___, ___SW3d___, 2009 WL 723182 (March 19, 2009) (“MERS, by the terms of the deed of trust, and its own stated purposes, was the lender’s agent”);

Thus, it is clear that MERS’s relationship with its member lenders is that of agent with principal. This is a fiduciary relationship, resulting from the manifestation of consent by one person to another, allowing the other to act on his behalf, subject to his control and consent. The principal is the one for whom action is to be taken, and the agent is the one who acts.It has been held that the agent, who has a fiduciary relationship with the principal, “is a party who acts on behalf of the principal with the latter’s express, implied, or apparent authority.” (Maurillo v Park Slope U-Haul, 194 AD2d 142, 146 [2d Dept 1992]). “Agents are bound at all times to exercise the utmost good faith toward their principals. They must act in accordance with the highest and truest principles of morality.” (Elco Shoe Mfrs. v Sisk, 260 NY 100, 103 [1932]). (See Sokoloff v Harriman Estates Development Corp., 96 NY 409 [2001]); Wechsler v Bowman, 285 NY 284 [1941]; Lamdin v Broadway Surface Advertising Corp., 272 NY 133 [1936]). An agent “is prohibited from acting in any manner inconsistent with his agency or trust and is at all times bound to exercise the utmost good faith and loyalty in the performance of his duties.” (Lamdin, at 136). Therefore, in the instant action, MERS, as nominee for CAMBRIDGE, is an agent of CAMBRIDGE for limited purposes. It can only have those powers given to it and authorized by its principal, CAMBRIDGE. Plaintiff ONEWEST has not submitted any documents demonstrating how CAMBRIDGE authorized MERS, as nominee for CAMBRIDGE, to assign the subject DRAYTON mortgage and note to INDYMAC, which subsequently assigned the subject mortgage and note to plaintiff ONEWEST. Recently, in Bank of New York v Alderazi,Lippincott v East River Mill & Lumber Co., 79 Misc 559 [1913]) and “[t]he declarations of an alleged agent may not be shown for the purpose of proving the fact of agency.” (Lexow & Jenkins, P.C. v Hertz Commercial Leasing Corp., 122 AD2d 25 [2d Dept 1986]; see also Siegel v Kentucky Fried Chicken of Long Is. 108 AD2d 218 [2d Dept 1985]; Moore v Leaseway Transp/ Corp., 65 AD2d 697 [1st Dept 1978].) “[T]he acts of a person assuming to be the representative of another are not competent to prove the agency in the absence of evidence tending to show the principal’s knowledge of such acts or assent to them.” (Lexow & Jenkins, P.C. v Hertz Commercial Leasing Corp., 122 AD2d at 26, quoting 2 NY Jur 2d, Agency and Independent Contractors § 26). Plaintiff has submitted no evidence to demonstrate that the original lender, the mortgagee America’s Wholesale Lender, authorized MERS to assign the secured debt to plaintiff. Therefore, in the instant action, plaintiff ONEWEST failed to demonstrate how MERS, as nominee for CAMBRIDGE, had authority from CAMBRIDGE to assign the DRAYTON mortgage to INDYMAC. The Court grants plaintiff ONEWEST leave to renew its motion for an order of reference, if plaintiff ONEWEST can demonstrate how MERS had authority from CAMBRIDGE to assign the DRAYTON mortgage and note to INDYMAC. Then, plaintiff ONEWEST must address the tangled employment situation of “robo-signer” Erica A. Johnson-Seck. She admitted in her July 9, 2010 deposition in the Machado case that she never provided me with affidavits of her employment for the prior three years and an explanation of why she wore so-many corporate hats in Maraj and Bethley. Further, in Deutsche Bank v Harris, Ms. Johnson-Seck executed an affidavit of merit as Vice President of Deutsche Bank. If plaintiff renews its motion for an order of reference, the Court must get to the bottom of Ms. Johnson-Seck’s employment status and her “robo-signing.” The Court reminds plaintiff ONEWEST’s counsel that Ms. Johnson-Seck, at p. 161 of the Machado deposition, volunteered, at lines 4-5 to “gladly show up in his court and provide him everything he wants.” Lastly, if plaintiff ONEWEST’S counsel moves to renew its application for an order of reference, plaintiff’s counsel must comply with the new filing requirement to submit, under penalties of perjury, an affirmation that he has taken reasonable steps, including inquiring of plaintiff ONEWEST, the lender, and reviewing all papers, to verify the accuracy of the submitted documents in support of the instant foreclosure action. According to yesterday’s Office of Court Administration press release, Chief Judge Lippman said: We cannot allow the courts in New York State to stand by idly and be party to what we now know is a deeply flawed process, especially when that process involves basic human needs — such as a family home — during this period of economic crisis. This new filing requirement will play a vital role in ensuring that the documents judges rely on will be thoroughly examined, accurate, and error-free before any judge is asked to take the drastic step of foreclosure. 28 Misc 3d at 379-380, my learned colleague, Kings County Supreme Court Justice Wayne Saitta explained that: A party who claims to be the agent of another bears the burden of proving the agency relationship by a preponderance of the evidence (

(See Gretchen Morgenson and Andrew Martin, Big Legal Clash on Foreclosure is Taking Shape, New York Times, Oct. 21, 2010; Andrew Keshner, New Court Rules Says Attorneys Must Verify Foreclosure Papers, NYLJ, Oct. 21, 2010).

Accordingly, it is

ORDERED, that the request of plaintiff ONEWEST BANK, F.S.B., to withdraw its motion for an order of reference, for the premises located at 962 Hemlock Street, Brooklyn, New York (Block 4529, Lot 116, County of Kings), is granted; and it is further

ORDERED, that the instant action, Index Number 15183/09, is dismissed without prejudice; and it is further

ORDERED, that the notice of pendency in the instant action, filed with the Kings County Clerk on June 18, 2009, by plaintiff ONEWEST BANK, F.S.B., to foreclose a mortgage for real property located at 962 Hemlock Street, Brooklyn, New York (Block 4529, Lot 116, County of Kings), is cancelled; and it is further

ORDERED, that leave is granted to plaintiff, ONEWEST BANK, F.S.B., to renew, within sixty (60) days of this decision and order, its motion for an order of reference for the premises located at 962 Hemlock Street, Brooklyn, New York (Block 4529, Lot 116, County of Kings), provided that plaintiff, ONEWEST BANK, F.S.B., submits to the Court: (1) proof of the grant of authority from the original mortgagee, CAMBRIDGE CAPITAL, LLC, to its nominee, MORTGAGE ELECTRONIC REGISTRATION SYSTEMS, INC., to assign the subject mortgage and note to INDYMAC FEDERAL BANK, FSB; and (2) an affidavit by Erica A. Johnson-Seck, Vice President of plaintiff ONEWEST BANK, F.S.B., explaining: her employment history for the past three years; why a conflict of interest does not exist in how she acted as a Vice President of assignor MORTGAGE ELECTRONIC REGISTRATION SYSTEMS, INC., a Vice President of assignee/assignor INDYMAC FEDERAL BANK, FSB, and a Vice President of assignee/plaintiff ONEWEST BANK, F.S.B. in this action; why she was a Vice President of both assignor MORTGAGE ELECTRONIC REGISTRATION SYSTEMS, INC. and assignee DEUTSCHE BANK in Deutsche Bank v Maraj, 18 Misc 3d 1123 (A) (Sup Ct, Kings County 2008); why she was a Vice President of both assignor MORTGAGE ELECTRONIC REGISTRATION SYSTEMS, INC. and assignee INDYMAC BANK, FSB in Indymac Bank, FSB, v Bethley, 22 Misc 3d 1119 (A) (Sup Ct, Kings County 2009); and, why she executed an affidavit of merit as a Vice President of DEUTSCHE BANK in Deutsche Bank v Harris (Sup Ct, Kings County, Feb. 5, 2008, Index No. 35549/07); and (3) counsel for plaintiff ONEWEST BANK, F.S.B. must comply with the new Court filing requirement, announced by Chief Judge Jonathan Lippman on October 20, 2010, by submitting an affirmation, using the new standard Court form, pursuant to CPLR Rule 2106 and under the penalties of perjury, that counsel for plaintiff ONEWEST BANK, F.S.B. has personally reviewed plaintiff ONEWEST BANK, F.S.B.’s documents and records in the instant action and counsel for plaintiff ONEWEST BANK, F.S.B. confirms the factual accuracy of plaintiff ONEWEST BANK, F.S.B.’s court filings and the accuracy of the notarizations in plaintiff ONEWEST BANK, F.S.B.’s documents.

This constitutes the Decision and Order of the Court.

[ipaper docId=40499638 access_key=key-1n9ja8i2jfczxnt1epea height=600 width=600 /]

Posted in STOP FORECLOSURE FRAUD3 Comments

![[NYSC] JUDGE SCHACK TAKES ON ROBO-SIGNER ERICA JOHNSON SECK: DEUTSCHE BANK v. HARRIS (2)](https://stopforeclosurefraud.com/wp-content/themes/gazette/thumb.php?src=wp-content/uploads/2010/10/Fraud_11.jpg&w=100&h=57&zc=1&q=90)

Posted on 29 March 2010.

Excerpt:

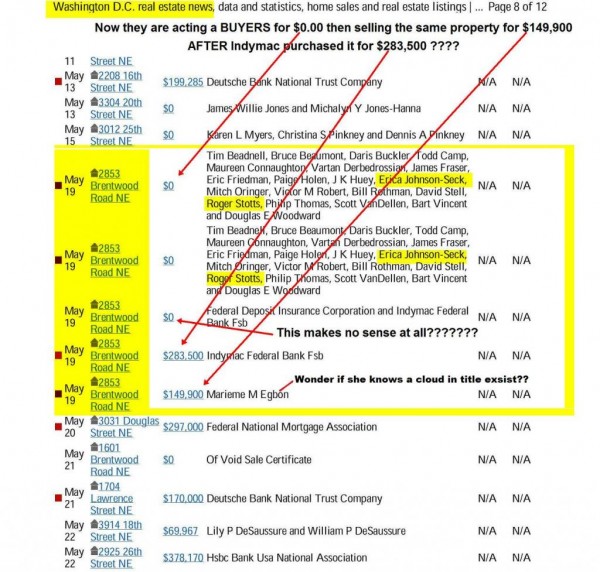

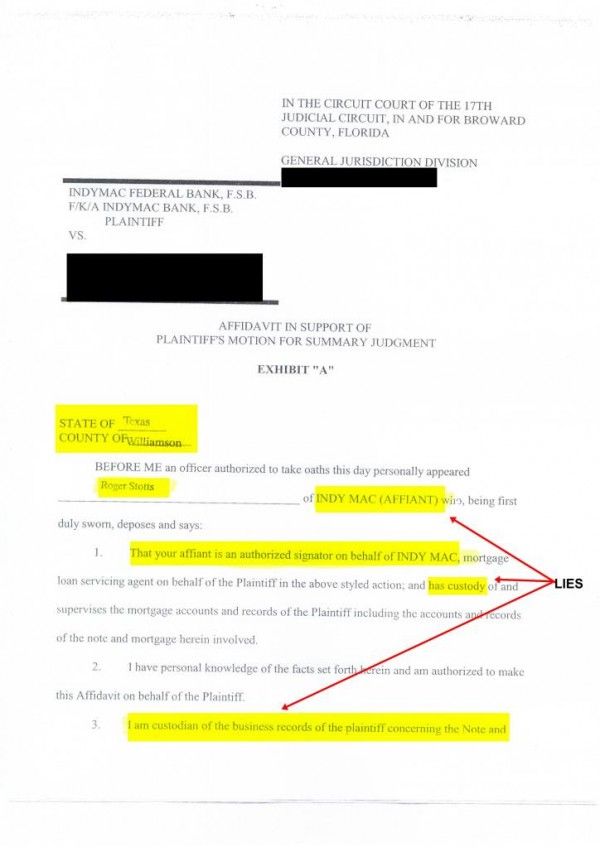

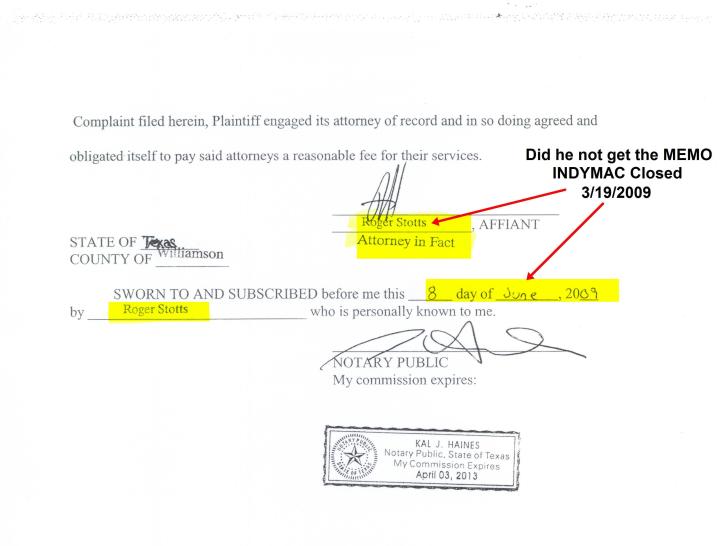

Plaintiffs affidavit, submitted in support of the instant application for a default judgment, was executed by Erica Johnson-Seck, who claims to be a Vice President of plaintiff DEUTSCHE BANK. The affidavit was executed in the State of Texas, County of Williamson (Williamson County, Texas is located in the Austin metropolitan area, and its county seat is Georgetown, Texas). The COURT is perplexed as to why the assignment was not executed in Pasadena, California, at 46U Sierra Madre Villa, the alleged “principal place of business” for both the assign1,)r and the assignee. In my January 3 1, 2008 decision (Deutsche Bank National Trust company v Maraj, – Misc 3d – [A], 2008 NY Slip Op 50176 [U]), I noted that Erica Johnson-Seck, claimed that she was a Vice President of MERS in her July 3,2007 INDYMAC to DEUTSCHE BANK assignment, and then in her July 3 1,2007 affidavit claimed to be a DEUTSCHE BANK Vice President. Just as in Deutsche Bank National Trust Company v Maraj, at 2, the Court in the instant action, before granting itn application for an order of reference, requires an affidavit from Ms. Johnson-Seck, describing her employment history for the past three years.

© 2010-19 FORECLOSURE FRAUD | by DinSFLA. All rights reserved.

Posted in STOP FORECLOSURE FRAUD0 Comments

![[NYSC] JUDGE SCHACK TAKES ON ROBO-SIGNER ERICA JOHNSON SECK: DEUTSCHE BANK v. MARAJ (1)](https://stopforeclosurefraud.com/wp-content/themes/gazette/thumb.php?src=wp-content/uploads/2010/10/002_arthur_schack-300x300.jpg&w=100&h=57&zc=1&q=90)

Posted on 26 March 2010.

2008 NY Slip Op 50176(U)

DEUTSCHE BANK NATIONAL TRUST COMPANY As Trustee under the Pooling and Servicing Agreement Series Index 2006-AR6, Plaintiff,

v.

RAMASH MARAJ A/K/A RAMISH MARAJ, ET AL., Defendants.

25981/07.

Supreme Court of the State of New York, Kings County.

Decided January 31, 2008.

Plaintiff: Kevin M. Butler, Esq., Eschen Frenkel Weisman & Gordon, De Rose & Surico, Bayside NY.

Defendant: No Opposition submitted by defendants to plaintiff’s Judgment of Foreclosure and Sale.

ARTHUR M. SCHACK, J.

Plaintiff’s application, upon the default of all defendants, for an order of reference for the premises located at 255 Lincoln Avenue, Brooklyn, New York (Block 4150, Lot 19, County of Kings) is denied without prejudice, with leave to renew upon providing the Court with a satisfactory explanation to various questions with respect to the July 3, 2007 assignment of the instant mortgage to plaintiff, DEUTSCHE BANK NATIONAL TRUST COMPANY AS TRUSTEE UNDER THE POOLING AND SERVICING AGREEMENT SERIES INDEX 2006-AR6 (DEUTSCHE BANK). The questions deal with: the employment history of one Erica Johnson-Seck, who assigned the mortgage to plaintiff DEUTSCHE BANK, and then subsequently executed the affidavit of facts in the instant application as an officer of DEUTSCHE BANK; plaintiff DEUTSCHE BANK’s purchase of the instant non-performing loan; and, why INDYMAC BANK, F.S.B., (INDYMAC), Mortgage Electronic Registration Systems, Inc. (MERS), and DEUTSCHE BANK all share office space at Building B, 901 East 104th Street, Suite 400/500, Kansas City, MO 64131 (Suite 400/500).

Defendant RAMASH MARAJ borrowed $440,000.00 from INDYMAC on March 7, 2006. The note and mortgage were recorded in the Office of the City Register, New York City Department of Finance on March 22, 2006 at City Register File Number (CRFN) XXXXXXXXXXXXX. INDYMAC, by Mortgage Electronic Registration Systems, Inc. (MERS), its nominee for the purpose of recording the mortgage, assigned the note and mortgage to plaintiff DEUTSCHE BANK, on July 3, 2007, with the assignment recorded on September 5, 2007 at CRFN XXXXXXXXXXXXX.

According to plaintiff’s application, defendant MARAJ’s default began with the nonpayment of principal and interest due on March 1, 2007. Yet on July 3, 2007, more than four months later, plaintiff DEUTSCHE BANK accepted the assignment of the instant non-performing loan from INDYMAC. Further, both assignor MERS, as nominee of INDYMAC, and assignee DEUTSCHE BANK list Suite 400/500 on the July 3, 2007 Assignment as their “principal place of business.” To compound corporate togetherness, page 2 of the recorded Assignment, lists the same Suite 400/500 as the address of INDYMAC.

The Assignment by MERS, on behalf of INDYMAC, was executed by Erica Johnson-Seck, Vice President of MERS. The notary public, Mai La Thao, stated in the jurat that the assignment was executed in the State of Texas, County of Williamson (Williamson County is located in the Austin metropolitan area, and its county seat is Georgetown, Texas). The Court is perplexed as to why the assignment was not executed in Kansas City, the alleged “principal place of business” for both the assignor and the assignee.

Twenty-eight days later, on July 31, 2007, the same Erica Johnson-Seck executed plaintiff’s affidavit submitted in support of the instant application for a default judgment. Ms. Johnson-Seck, in her affidavit, states that she is “an officer of Deutsche Bank National Trust Company as Trustee under the Pooling and Servicing Agreement Series INDX 2006-AR6, the plaintiff herein.” At the end of the affidavit she states that she is a Vice President of DEUTSCHE BANK. Again, Mai La Thao is the notary public and the affidavit is executed in the State of Texas, County of Williamson. The Erica Johnson-Seck signatures on both the July 3, 2007 assignment and the July 31, 2007 affidavit are identical. Did Ms. Johnson-Seck change employers from July 3, 2007 to July 31, 2007, or does she engage in self-dealing by wearing two corporate hats? The Court is concerned that there may be fraud on the part of plaintiff DEUTSCHE BANK, or at least malfeasance. Before granting an application for an order of reference, the Court requires an affidavit from Ms. Johnson-Seck, describing her employment history for the past three years.

Further, the Court requires an explanation from an officer of plaintiff DEUTSCHE BANK as to why, in the middle of our national subprime mortgage financial crisis, DEUTSCHE BANK would purchase a non-performing loan from INDYMAC, and why DEUTSCHE BANK, INDYMAC and MERS all share office space in Suite 400/500.

With the assignor MERS and assignee DEUTSCHE BANK appearing to be engaged in possible fraudulent activity by: having the same person execute the assignment and then the affidavit of facts in support of the instant application; DEUTSCHE BANK’s purchase of a non-performing loan from INDYMAC; and, the sharing of office space in Suite 400/500 in Kansas City, the Court wonders if the instant foreclosure action is a corporate “Kansas City Shuffle,” a complex confidence game. In the 2006 film, Lucky Number Slevin, Mr. Goodkat, (a hitman played by Bruce Willis), explains (in memorable quotes from Lucky Number Slevin, at www.imdb.com/title/tt425210/quotes).

A Kansas City Shuffle is when everybody looks right, you go left . . .

It’s not something people hear about. Falls on deaf ears mostly . . .

No small matter. Requires a lot of planning. Involves a lot of people. People connected by the slightest of events. Like whispers in the night, in that place that never forgets, even when those people do.

In this foreclosure action is plaintiff DEUTSCHE BANK, with its “principal place of business” in Kansas City attempting to make the Court look right while it goes left?

Accordingly, it is

ORDERED, that the application of plaintiff, DEUTSCHE BANK NATIONAL TRUST COMPANY AS TRUSTEE UNDER THE POOLING AND SERVICING AGREEMENT SERIES INDEX 2006-AR6, for an order of reference for the premises located at 255 Lincoln Avenue, Brooklyn, New York (Block 4150, Lot 19, County of Kings), is denied without prejudice; and it is further

ORDERED, that leave is granted to plaintiff, DEUTSCHE BANK NATIONAL TRUST COMPANY AS TRUSTEE UNDER THE POOLING AND SERVICING AGREEMENT SERIES INDEX 2006-AR6, to renew its application for an order of reference for the premises located at 255 Lincoln Avenue, Brooklyn, New York (Block 4150, Lot 19, County of Kings), upon presentation to the Court, within forty-five (45) days of this decision and order, of: an affidavit from Erica Johnson-Seck describing her employment history for the past three years; and, an affidavit from an officer of plaintiff

DEUTSCHE BANK NATIONAL TRUST COMPANY AS TRUSTEE UNDER THE POOLING AND SERVICING AGREEMENT SERIES INDEX 2006-AR6, explaining why (1) plaintiff purchased a nonperforming loan from INDYMAC BANK, F.S.B., (2) shares office space at Building B, 901 East 104th Street, Suite 400/500, Kansas City, MO 64131 with Mortgage Electronic Registration Systems, Inc. and INDYMAC BANK, F.S.B., and (3), claims Building B, 901 East 104th Street, Suite 400/500, Kansas City, MO 64131 as its principal place of business in the Assignment of the instant mortgage and yet executed the Assignment and affidavit of facts in this action in Williamson County, Texas.

This constitutes the Decision and Order of the Court.

[ipaper docId=40494321 access_key=key-18trq6o8869pcgoq0lxh height=600 width=600 /]

© 2010-19 FORECLOSURE FRAUD | by DinSFLA. All rights reserved.Posted in STOP FORECLOSURE FRAUD0 Comments

Posted on 02 March 2010.

This is a Must Read where ICE Legal from Palm Beach rips into Ms. Seck…

Picture says it all!

Here, Plaintiff and Plaintiff’s counsel misled the Court about the real party in interest in the case; and 2) engaged in extensive discovery abuse to obstruct revelation of the

known falsities in the complaint – a “flagrant abuse of the judicial process” worthy of severe sanctions. See Martin v. Automobili Lamborghini Exclusive, Inc., 307 F.3d 1332 (11th Cir. 2002). Dismissal for fraud is appropriate where “a party has sentiently set in motion some unconscionable scheme calculated to interfere with the judicial system’s ability impartially to adjudicate a matter by improperly influencing the trier of fact or unfairly hampering the presentation of the opposing party’s claim or defense.” Cox v. Burke, 706 So.2d 43, 46 (Fla. 5th DCA 1998).

Yep you gone done it again…This time you messed with the WRONG assignments…MINE!!!

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LoSPTjd_PXM]

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SD6XUboT1JM]

DEPOSITION OF ERICA JOHNSON-SECK by DinSFLA on Scribd

Here is her peers doing the same…

Posted in concealment, conspiracy, corruption, fraud digest, Law Offices Of David J. Stern P.A., Lender Processing Services Inc., LPS, MERS, Mortgage Foreclosure Fraud, scam3 Comments

Posted on 04 July 2011.

2011 NY Slip Op 31748(U)

20049/08, Motion Cal. No. 12, Motion Seq. No. 5.

Supreme Court, Queens County.

June 23, 2011.

BERNICE D. SIEGAL, Judge.

EXCERPTS:

Approximately ten months after the stipulation was entered into, Plaintiff set a new sale date of February 18, 2011. Defendant Garcia now moves for an order seeking to vacate the terms of the stipulation, vacate the default judgment and renew the original order to show cause, predominantly upon the grounds that the Affidavit of Amount Due is signed by Erica A. Johnson-Seck, (hereinafter Johnson-Seck”) Vice-President, an alleged “Robo-Signer.”

[…]

Garcia moves for an order to renew its original order to show cause which sought to vacate the default judgment based on alleged fraud on behalf of the plaintiff. (CPLR §5015(a)(3).) Garcia asserts that the recent discovery of alleged fraud in the preparation of Plaintiff’s affidavit to secure the Judgment of Foreclosure and Sale is sufficient basis to renew it’s prior order to show cause to vacate the default judgment.

Garcia asserts that Johnson-Seck is a confirmed robo-signer as evidenced by recent published decisions. (See Onewest Bank, F.S.B. v Drayton, 29 Misc 3d 1021 [Sup.Ct. Kings County 2010]; see also Indymac Bank, FSB v. Bethley, 22 Misc.3d 1119(A) [Sup.Ct. Kings County 2009].) “A `robo-signer’ is a person who quickly signs hundreds or thousands of foreclosure documents in a month, despite swearing that he or she has personally reviewed the mortgage documents and has not done so.” (Onewest Bank, F.S.B. v Drayton, 29 Misc 3d 1021 [Sup.Ct. Kings County 2010].)

Plaintiff, in opposition, does not refute defendant’s assertion that Johnson-Seck is a “robo-signer,” rather, Plaintiff asserts that accusations regarding Johnson-Seck were made public prior to the execution of the aforementioned stipulation, dated March 24, 2010, and therefore any alleged fraud or mistake was known or knowable to defendant’s attorney. “The requirement that a motion for renewal be based upon newly-discovered facts is a flexible one, and a court, in its discretion, may grant renewal upon facts known to the moving party at the time of the original motion.” (Karlin v. Bridges, 172 A.D.2d 644 [2nd Dept 1991].) Even if the court assumes that Garcia’s counsel, David Fuster, Esq., should have known of Johnson-Seck’s “robo-signing,” it is still not a complete defense to Garcia’s motion. Accordingly, Garcia’s motion to renew is granted.

Upon renewal this court vacates the prior default judgment dated February 23, 2009, and the stipulation dated March 24, 2010.

CPLR § 3215(f) states:

On any application for judgment by default, the applicant shall file … proof of the facts constituting the claim, the default and the amount due by affidavit made by the party.

Plaintiff submits a “reverified” Affidavit of Charlotte Warwick (hereinafter “Warwick”) attesting that the principal amount due on Garcia’s loan is $472,326.52. Plaintiff contends that the Warwick affidavit cures the fraudulent Affidavit of Amount Due submitted by Johnson-Seck. However, the Judgment of Foreclosure and aforementioned Stipulation, dated March 24, 2010, where all signed under the assumption that the plaintiff had originally submitted non-fraudulent documentation. So while the fraudulent Affidavit of Amount Due may be a curable defect, the court cannot ignore the fact that the papers supporting the Judgment of Foreclosure and Sale and aforementioned stipulation were fraudulent.

In addition, a default judgment obtained through “extrinsic fraud,” which is “a fraud practiced in obtaining a judgment such that a party may have been prevented from fully and fairly litigating the matter” does not require the defendant to prove a reasonable excuse for such default. (Bank of New York v. Lagakos, 27 A.D.3d 678 [2nd Dept 2006] citing Shaw v. Shaw, 97 A.D.2d 403 [2nd Dept 1983].)

Furthermore, the court is concerned by Plaintiff’s position that the “events he (Garcia) complains of… make no factual difference to the amount he owes on his mortgage.” The statement is alarming as it implies that the court should ignore fraud when the fraud may not be directly relevant to the outcome of the particular case. The court requires an Affidavit of Amount Due and that requirement cannot be satisfied by submitting a fraudulent affidavit. (Indymac Bank, FSB v. Bethley, 22 Misc.3d 1119 [Sup.Ct. Kings County 2009] [prior to granting an application for an order of reference, the Court required an affidavit from Ms. Johnson-Seck, describing her employment history for the past three years].) Plaintiff has failed to deny defendant’s contention that the Johnson-Seck document was fraudulent. Therefore, the Plaintiff failed to submit “proof of the facts constituting the claim, the default and the amount due by affidavit made by the party” as required by CPLR §3215(f).

However, before the judgment on default can be vacated, the settlement stipulation must be vitiated.”Only where there is cause sufficient to invalidate a contract, such as fraud, collusion, mistake or accident, will a party be relieved from the consequences of a stipulation made during litigation” (Hallock v. State, 64 N.Y.2d 224 (1984.) “It is the party seeking to set aside the stipulation … who has the burden of showing that the agreement was the result of fraud.” (Sweeney v. Sweeney, 71 A.D.3d 989 [2nd Dept 2010].) As noted earlier, the fraud perpetrated by the Plaintiff had a domino effect that lead Garcia ultimately to enter into the stipulation. Garcia entered into the agreement on March 24, 2010 to avoid an immediate foreclosure he believed was obtained legally. Accordingly, Garcia has sufficiently established his burden by showing that he would not have entered the stipulation had he known that the Affidavit in support of the default judgment (vacated herein) was fraudulent.

Based on the foregoing, Garcia’s motion is granted to the extent of granting renewal and upon renewal granting the order to show cause dated August 27, 2009 vacating the default judgment of foreclosure and sale entered by this court on or about February 23, 2009 and the stipulation dated March 24, 2010 is declared null and void.

[…]

After you read the brief below, check out more on Ms. Johnson-Seck

Full Deposition Of ERICA JOHNSON SECK Former Fannie Mae, WSB Employee

[NYSC] JUDGE SCHACK TAKES ON ROBO-SIGNER ERICA JOHNSON SECK: DEUTSCHE BANK v. MARAJ (1) (64.591)

[NYSC] JUDGE SCHACK TAKES ON ROBO-SIGNER ERICA JOHNSON SECK: DEUTSCHE BANK v. HARRIS (2) (70.24)

[NYSC] JUDGE SCHACK TAKES ON ROBO-SIGNER ERICA JOHNSON SECK: ONEWEST BANK v. DRAYTON (3)

Wall Street Journal: Foreclosure? Not So Fast

ONEWEST BANK ‘ERICA JOHNSON-SECK’ ‘Not more than 30 seconds’ to sign each foreclosure document

INDYMAC’S/ONEWEST FORECLOSURE ‘ROBO-SIGNERS’ SIGNED 24,000 MORTGAGE DOCUMENTS MONTHLY

WM_Deposition_of_Erica_Johnson-Seck_Part_I

Deposition_of_Erica_Johnson-Seck_Part_II

Yep, she signs for FDIC too!

[ipaper docId=59328304 access_key=key-2b848aadh4jpp9xz8vzi height=600 width=600 /]

© 2010-19 FORECLOSURE FRAUD | by DinSFLA. All rights reserved.Posted in STOP FORECLOSURE FRAUD0 Comments

Posted on 30 September 2010.

The recent announcements by J.P. Morgan Chase and Ally Financial that they were freezing some foreclosures because of paperwork irregularities raises a key question: How many more mortgage companies employed “robo-signers?”

In a sworn deposition in July, Erica Johnson-Seck, an Austin, Tex.,-based vice president for bankruptcy and foreclosure for OneWest Bank, said she and her team of seven others sign 6,000 documents a week or about 24,000 a month without reading all of them.

Johnson-Seck estimated that she spent no more than 30 seconds to sign each document.

She explained that while she does not check everything, she does check some information, “which is why I said 30 seconds instead of two seconds.”

.

© 2010-19 FORECLOSURE FRAUD | by DinSFLA. All rights reserved.Posted in chain in title, CONTROL FRAUD, corruption, deed of trust, eric friedman, erica johnson seck, foreclosure, foreclosure fraud, foreclosure mills, foreclosures, indymac, investigation, Law Offices Of David J. Stern P.A., MERS, MERSCORP, mortgage, MORTGAGE ELECTRONIC REGISTRATION SYSTEMS INC., robo signers, roger stotts, stopforeclosurefraud.com, Trusts1 Comment

Posted on 26 March 2010.

via b.daviesmd6605

SAME RESPONSES OBJECTIONS AND NO DOCUMENTS. IT IS THE GAME. HOPEFULLY WE CAN BREAK THIS GAME. WE ALL HAVE ERICA JOHNSON-SECKS DEPOSITION. JUST FOLLOW THE YELLOW BRICK ROAD.

[ipaper docId=28942482 access_key=key-q7xsg1ugun6de39c0wi height=600 width=600 /]

© 2010-19 FORECLOSURE FRAUD | by DinSFLA. All rights reserved.Posted in concealment, conspiracy, corruption, erica johnson seck, indymac, MERS, MORTGAGE ELECTRONIC REGISTRATION SYSTEMS INC., onewest0 Comments

Posted on 20 March 2010.

Indymac Federal Bank Fsb Vs. Israel a. Machado :

In this depo you will see exactly how this Illegal FORECLOSURE FRAUD is fabricated, conspired, concealed, manipulated and fraud upon the courts.

Deposition_of_Erica_Johnson-Seck_Part_I

[ipaper docId=37528161 access_key=key-t6hhb0aqxj8gvgam8s7 height=600 width=600 /]

© 2010-19 FORECLOSURE FRAUD | by DinSFLA. All rights reserved.Posted in concealment, conspiracy, corruption, erica johnson seck, FIS, foreclosure fraud, foreclosure mills, fraud digest, indymac, Lender Processing Services Inc., LPS, MERS, MERSCORP, MORTGAGE ELECTRONIC REGISTRATION SYSTEMS INC., Mortgage Foreclosure Fraud, note, onewest0 Comments

Posted on 20 June 2013.

I wonder if Erica Johnson Seck & Roger Stotts will be on the list amongst others who worked for IndySmack in the days?

Whistle-Blowers to the front of the line.

Abc Local-

Executives with OneWest Bank have announced that more than 700 workers will lose their jobs as the company is acquired as part of a $2.53 billion deal.

The Austin American-Statesman reports Monday that the majority of the 725 employees work at a call center.

© 2010-19 FORECLOSURE FRAUD | by DinSFLA. All rights reserved.Posted in STOP FORECLOSURE FRAUD1 Comment

Posted on 01 April 2012.

NYT-

Federal regulators are poised to crack down on eight financial firms that are not part of the recent government settlement over home foreclosure practices involving sloppy, inaccurate or forged documents.

Last week, a senior Federal Reserve official recommended fines for these additional financial institutions, raising questions about how deep foreclosure problems run through the banking industry.

In addition, judges, lawyers and advocates for homeowners say that people are still losing their homes despite improper documentation and other flaws in the foreclosure process often involving these firms.

The eight firms cited by the Federal Reserve — HSBC’s United States bank division, SunTrust Bank, MetLife, U.S. Bancorp, PNC Financial Services, EverBank, OneWest and Goldman Sachs — should be fined for “unsafe and unsound practices in their loan servicing and foreclosure processing,” Suzanne G. Killian, a senior associate director of the Federal Reserve’s Division of Consumer and Community Affairs, told lawmakers last month in a House Oversight Committee hearing in Brooklyn.

Click here to read Judge Schack Slams Foreclosure Firm Rosicki, Rosicki & Associates, P.C. “Conflicted Robosigner Kim Stewart”, the case mentioned in the article.

Click here to read about robo-signer Marti Noriega in OREGON DISTRICT COURT ISSUES A TRO AGAINST MERS, BofA and LITTON, the case mentioned in the article.

Last from this article is the one and only Erica Johnson-Seck…

Full Deposition Of ERICA JOHNSON SECK Former Fannie Mae, WSB Employee

[NYSC] JUDGE SCHACK TAKES ON ROBO-SIGNER ERICA JOHNSON SECK: DEUTSCHE BANK v. MARAJ (1) (64.591)

[NYSC] JUDGE SCHACK TAKES ON ROBO-SIGNER ERICA JOHNSON SECK: DEUTSCHE BANK v. HARRIS (2) (70.24)

[NYSC] JUDGE SCHACK TAKES ON ROBO-SIGNER ERICA JOHNSON SECK: ONEWEST BANK v. DRAYTON (3)

Wall Street Journal: Foreclosure? Not So Fast

ONEWEST BANK ‘ERICA JOHNSON-SECK’ ‘Not more than 30 seconds’ to sign each foreclosure document

INDYMAC’S/ONEWEST FORECLOSURE ‘ROBO-SIGNERS’ SIGNED 24,000 MORTGAGE DOCUMENTS MONTHLY

WM_Deposition_of_Erica_Johnson-Seck_Part_I

Deposition_of_Erica_Johnson-Seck_Part_II

© 2010-19 FORECLOSURE FRAUD | by DinSFLA. All rights reserved.Posted in STOP FORECLOSURE FRAUD2 Comments

Posted on 05 August 2011.

Make sure you catch who signed the assignment of mortgage down below… but ERICA JOHNSON-SECK!

Credit Slips–

A major issue arising in foreclosure defense cases is the homeowner’s ability to challenge the foreclosing party’s standing based on noncompliance with securitization documentation. Several courts have held that there is no standing to challenge standing on this basis, most recently the 1st Circuit BAP in Correia v. Deutsche Bank Nat’l Trust Company. (See Abigail Caplovitz Field’s cogent critique of that ruling here.) The basis for these courts’ rulings is that the homeowner isn’t a party to the PSA, so the homeowner has no standing to raise noncompliance with the PSA.

I think that view is plain wrong. It fails to understand what PSA-based foreclosure defenses are about and to recognize a pair of real and cognizable Article III interests of homeowners: the right to be protected against duplicative claims and the right to litigate against the real party in interest because of settlement incentives and abilities.

ERICA JOHNSON-SECK

Full Deposition Of ERICA JOHNSON SECK Former Fannie Mae, WSB Employee

[NYSC] JUDGE SCHACK TAKES ON ROBO-SIGNER ERICA JOHNSON SECK: DEUTSCHE BANK v. MARAJ (1) (64.591)

[NYSC] JUDGE SCHACK TAKES ON ROBO-SIGNER ERICA JOHNSON SECK: DEUTSCHE BANK v. HARRIS (2) (70.24)

[NYSC] JUDGE SCHACK TAKES ON ROBO-SIGNER ERICA JOHNSON SECK: ONEWEST BANK v. DRAYTON (3)

Wall Street Journal: Foreclosure? Not So Fast

ONEWEST BANK ‘ERICA JOHNSON-SECK’ ‘Not more than 30 seconds’ to sign each foreclosure document

INDYMAC’S/ONEWEST FORECLOSURE ‘ROBO-SIGNERS’ SIGNED 24,000 MORTGAGE DOCUMENTS MONTHLY

Thank you to Mike Dillon for pointing and providing this crucial piece below

[ipaper docId=61704717 access_key=key-16i71qddg7jbehlsos7g height=600 width=600 /]

© 2010-19 FORECLOSURE FRAUD | by DinSFLA. All rights reserved.Posted in STOP FORECLOSURE FRAUD1 Comment

Posted on 03 October 2010.

By now, most have read the Deposition of the Infamous Erica Johnson Seck. This is the homeowner Israel Machado speaking out about his foreclosure.

Thank you Ice Legal!

LOXAHATCHEE, Fla.—Israel Machado’s foreclosure started out as a routine affair. In the summer of 2008, as the economy began to soften, Mr. Machado’s pool-cleaning business suffered and like millions of other Americans, he fell behind on his $400,000 mortgage.

But Mr. Machado’s response was unlike most other Americans’. Instead of handing his home over to the lender, IndyMac Bank FSB, he hired Ice Legal LP in nearby Royal Palm Beach to fight the foreclosure. The law firm researched the history of Mr. Machado’s loan and found two interesting facts.

First, the affidavits IndyMac used to file the foreclosure were signed by a so-called robo-signer named Erica A. Johnson-Seck, who routinely signed 6,000 documents a week related to foreclosures and bankruptcy. That volume, the court decided, meant Ms. Johnson-Seck couldn’t possibly have thoroughly reviewed the facts of Mr. Machado’s case, as required by law.

Secondly, IndyMac (now called OneWest Bank) no longer owned the loan—a group of investors in a securitized trust managed by Deutsche Bank did. Determining that IndyMac didn’t really have standing to foreclose, a judge threw out the case and ordered IndyMac to pay Mr. Machado’s $30,000 legal bill.

Mr. Machado and his lawyer, Tom Ice, say they now want to convince the owners of the mortgage to cut Mr. Machado’s loan balance to between $150,000 and $200,000—the current selling price for comparable homes in his community near West Palm Beach. “The whole intent was to get them to come to the negotiating table, to get me in a fixed-rate mortgage that worked,” Mr. Machado said.

.

© 2010-19 FORECLOSURE FRAUD | by DinSFLA. All rights reserved.Posted in assignment of mortgage, bogus, Bryan Bly, CONTROL FRAUD, deposition, deutsche bank, erica johnson seck, foreclosure, foreclosure fraud, indymac, note, onewest, robo signers1 Comment

Posted on 27 September 2010.

Please welcome Ericka Johnson Seck to the ROBO-SIGNER Hall of Sham!

Here is a list of her many Corporate Hats:

I must confess, she was my first study because she signed two assignments for “one” of my properties using “two” different employers. 🙂 ‘<blush> I even created my very first youtube video in her honor (see below)!

Thanks to Judge Arthur Schack and Tom Ice from Ice Legal in Palm Beach County, we all became familiar with Erica for wearing too many corporate hats.

She is the “Robo-Signer” Judge Schack called out in three particular cases in NY and made her an instant foreclosure household name. I don’t think she ever emerged in NY soon after this. Also see the HSCB v. Yasmin case.

The Court is perplexed as to why the assignment was not executed in Pasadena, California, at 46U Sierra Madre Villa, the alleged “principal place of business” for both the assignor and the assignee. In my January 3 1, 2008 decision (Deutsche Bank National Tr (1st Canpuny v Maraj, – Misc 3d – [A], 2008 NY Slip Op 50176 [U]), I noted that Erica Johnson-Seck, claimed that she was a Vice President of MERS in her July 3,2007 INDYMAC to DEUTSCHE BANK assignment, and then in her July 3 1,2007 affidavit claimed to be a DEUTSCHE BANK Vice President. Just as in Deutsche Bank National Trust Company v Maraj, at 2, the Court in the instant action, before granting itn application for an order of reference, requires an affidavit from Ms. Johnson-Seck, describing her employment history for the past three years.

Further, the Court requires an explanation from an officer of plaintiff DEUTSCHE BANK as to why, in the middle of our national subprime mortgage financial crisis, DEUTSCHE BANK would purchase a non-perferforming loan from INDYMAC, and why DEUTSCHE BANK, INDYMAC and MERS all share office space at 460 Sierra Madre Villa, Pasadena, CA 91 107.

Now Lets move on to this below… according to this deposition her office signs 24,000 mortgage related documents out of the this figure she signed about “750” a week making it approximately 3000 mortgage documents used in foreclosure cases. Anything from Affidavits of Debt, Lost Note Affidavits, Assignment of Mortgages, Declarations pretty much anything having to deal with Bankruptcy and Foreclosures.

[ipaper docId=37528161 access_key=key-t6hhb0aqxj8gvgam8s7 height=600 width=600 /]

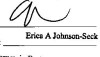

Below is a sale that happened in DC all in 1 single day! It appears she also puts properties in her name with her co-employees Roger Stotts and Eric Friedman.

© 2010-19 FORECLOSURE FRAUD | by DinSFLA. All rights reserved.FIRST VIDEO MADE OF DAVID J. STERN, ERICA JOHNSON-SECK BACK IN FEBRUARY 2010

Posted in assignment of mortgage, bogus, CONTROL FRAUD, corruption, deposition, deutsche bank, erica johnson seck, fdic, foreclosure, foreclosure fraud, foreclosure mills, foreclosures, Former Fidelity National Information Services, investigation, judge arthur schack, Law Offices Of David J. Stern P.A., lis pendens, MERS, MERSCORP, Moratorium, MORTGAGE ELECTRONIC REGISTRATION SYSTEMS INC., notary fraud, note, onewest, robo signers, roger stotts, STOP FORECLOSURE FRAUD, stopforeclosurefraud.com12 Comments

Posted on 07 September 2010.

Last updated- 3/27/2014

.

.

DEPOSITION OF FRANK A. DEAN – JP MORGAN CHASE – Home loan research officer

________________________________________

________________________________________

________________________________________

Full Deposition of Northwest Trustee Services YVONNE McELLIGOTT

Full Deposition of Northwest Trustee Services JEFF STENMAN

____________________________________

____________________________________

____________________________________

____________________________________

____________________________________

____________________________________

DEPOSITION TRANSCRIPT OF DAVID J. STERN ESQ. FROM 1/19/2000 BRYANT v. STERN

____________________________________

Full Deposition Transcript of ROY DIAZ Shareholder of Smith, Hiatt & Diaz, P.A. Law Firm

____________________________________

Deposition Transcript of Litton Loan Servicing Litigation Manager Christopher Spradling

____________________________________

Deposition Transcript of SELECT PORTFOLIO SERVICING (SPS) MINDY LEETHAM

____________________________________

DEPOSITION TRANSCRIPT OF DEUTSCHE BANK NATIONAL TRUST VP RONALDO REYES

____________________________________

Deposition Transcript of DOCx, LPS CHERYL DENISE THOMAS

DEPOSITION TRANSCRIPT OF LPS/ FIDELITY BILL NEWLAND

FULL DEPOSITION TRANSCRIPT OF LENDER PROCESSING SERVICES “LPS” SCOTT A. WALTER PART 1

FULL DEPOSITION TRANSCRIPT OF LPS GREG ALLEN “MERS IS ALIVE”

____________________________________

DEPOSITION TRANSCRIPT OF “SHELLIE HILL” OF LERNER, SAMPSON & ROTHFUSS LS&R

____________________________________

FULL DEPOSITION TRANSCRIPT OF ALDEN BERNER WELLS FARGO

____________________________________

FULL DEPOSITION TRANSCRIPT OF COUNTRYWIDE BofA LINDA DiMARTINI

____________________________________

FULL DEPOSITION OF FLORIDA DEFAULT LAW GROUP MANAGING PARTNER RONALD WOLFE

____________________________________

FULL DEPOSITION OF CITI RESIDENTIAL, AMC TAMARA PRICE

____________________________________

____________________________________

VIDEO DEPOSITION OF NATIONWIDE TITLE CLEARING BRYAN BLY

Citi Residential Deposition of Bly, Brian depo with attch[1]

SFF EXCLUSIVE: VIDEO DEPOSITION OF NATIONWIDE TITLE CRYSTAL MOORE

VIDEO DEPOSITION OF NATIONWIDE TITLE CLEARING DHURATA DOKO

FULL DEPOSITION TRANSCRIPT OF NATIONWIDE TITLE CLEARING ERICA LANCE BRYAN BLY

____________________________________

FULL DEPOSITION OF LAW OFFICES OF DAVID J. STERN BETH CERNI

____________________________________

FULL DEPOSITION TRANSCRIPT OF HOLLAN FINTEL FORMER FLORIDA DEFAULT LAW GROUP ATTORNEY

____________________________________

WM_FULL DEPOSITION TRANSCRIPT OF WELLS FARGO TAMARA SAVERY

____________________________________

WM FULL-DEPOSITION-TRANSCRIPT-OF-MARY-CARDOVA-OF-LAW-OFFICES-OF-DAVID-J.-STERN

____________________________________

WM_FULL DEPOSITION TRANSCRIPT OF KELLY SCOTT OF LAW OFFICES OF DAVID J. STERN

____________________________________

WM_FULL_DEPOSITION_OF_RESIDENTIAL FUNDING.GMAC_JUDY_FABER

____________________________________

WM_FULL_DEPOSITION_TRANSCRIPT_OF_BANK_OF_AMERICA_RENEE_D_HERTZLER

____________________________________

Full-Deposition-of-Wells_Fargo_John-Herman-Kennerty

____________________________________

WM_Full-Deposition-of-Tammie-Lou-Kapusta-Law-Office-of-David-J-Stern

____________________________________

WM_Deposition_of_Erica_Johnson-Seck_Part_I

Deposition_of_Erica_Johnson-Seck_Part_II

IndyMac Deposition of Johnson Seck, Erica Wagstaff v IndyMac

____________________________________

TAKE TWO NEW FULL DEPOSITION OF CHERYL SAMONS

Cheryl Samons 1st Depo from 2009

____________________________________

BETH COTTRELL CHASE HOME FINANCE

____________________________________

EXHIBIT G Chase Deposition of Herndon, Charles 10-06-09

____________________________________

FULL DEPOSITION OF DAVID J. STERN’S SHANNON SMITH

____________________________________

____________________________________

Deposition_Of_Jeffrey_Stephan_2_Maine

____________________________________

____________________________________

____________________________________

____________________________________

DEPOSITION OF FRANCIS S. HALLINAN, ESQUIRE “HIRED BY WELLS FARGO?”

____________________________________

MERS R.K. ARNOLD 2006 depo 9252006

MERS DEPO OF CEO RK Arnold 2009

MERS DEPOSITION OF WILLIAM Hultman

MERS VP William Hultman Deposition NJ

________________________________

If any of these depositions help you, please consider making a donation to help fund the activities and costs associated in up-keeping this site.

I welcome your donations via my secure PayPal link. You can use your VISA, Mastercard, American Express or Discover Card, so donating is fast and easy.

But you don’t have to set up a PayPal account to donate here. One-time donations are easy too.

Posted in 2 Comments

Posted on 04 March 2010.

If self nominating officers signing on

behalf of MERS, et al~ wasn’t good

enough…

Washington, D.C., February 24, 2010: Although only bankers are aware of it, there is a second wave of economic disaster starting to build up that will make the earlier one pale into insignificance. Let us start out with MERS, shall we?