In re: NILES C. TAYLOR; ANGELA J. TAYLOR, Debtors

ROBERTA A. DEANGELIS, Acting United States Trustee, Appellant.

No. 10-2154.

United States Court of Appeals, Third Circuit.

Argued: March 22, 2011. Opinion Filed: August 24, 2011.

Frederic J. Baker, Esq., Robert J. Schneider, Esq., George M. Conway, Esq., United States Department of Justice, Office of the United States Trustee, 833 Chestnut St., Suite 500, Philadelphia, PA 19107.

Ramona Elliott, Esq., P. Matthew Sutko, Esq., John P. Sheahan, Esq. (argued), United States Department of Justice, Executive Office for United States Trustees, 20 Massachusetts Ave. NW, Suite 8100, Washington, DC 20530, Attorneys for Appellant.

Jonathan J. Bart, Esq. (argued), Wilentz Goldman & Spitzer, P.A., Two Penn Center Plaza, Suite 910, Philadelphia, PA 19102, Attorney for Appellees.

Before: FUENTES, SMITH and VAN ANTWERPEN, Circuit Judges.

OPINION

FUENTES, Circuit Judge.

The United States Trustee, Region 3 (“Trustee”), appeals the reversal by the District Court of sanctions originally imposed in the bankruptcy court on attorneys Mark J. Udren and Lorraine Doyle, the Udren Law Firm, and HSBC for violations of Federal Rule of Bankruptcy Procedure 9011. For the reasons given below, we will reverse the District Court and affirm the bankruptcy court’s imposition of sanctions with respect to Lorraine Doyle, the Udren Law Firm, and HSBC.[1] However, we will affirm the District Court’s reversal of the bankruptcy court’s sanctions with respect to Mark J. Udren.

I.

A. Background

This case is an unfortunate example of the ways in which overreliance on computerized processes in a high-volume practice, as well as a failure on the part of clients and lawyers alike to take responsibility for accurate knowledge of a case, can lead to attorney misconduct before a court. It arises from the bankruptcy proceeding of Mr. and Ms. Niles C. and Angela J. Taylor. The Taylors filed for a Chapter 13 bankruptcy in September 2007. In the Taylors’ bankruptcy petition, they listed the bank HSBC, which held the mortgage on their house, as a creditor. In turn, HSBC filed a proof of claim in October 2007 with the bankruptcy court.

We are primarily concerned with two pleadings that HSBC’s attorneys filed in the bankruptcy court—(1) the request for relief from the automatic stay which would have permitted HSBC to pursue foreclosure proceedings despite the Taylors’ bankruptcy filing and (2) the response to the Taylors’ objection to HSBC’s proof of claim. We are also concerned with the attorneys’ conduct in court in connection with those pleadings. We draw our facts from the findings of the bankruptcy court.

1. The proof of claim (Moss Codilis law firm)

To preserve its interest in a debtor’s estate in a personal bankruptcy case, a creditor must file with the court a proof of claim, which includes a statement of the claim and of its amount and supporting documentation. Tennessee Student Assistance Corp. v. Hood, 541 U.S. 440, 447 (2004); Fed. R. Bank. P. 3001; Official Bankruptcy Form 10. In October 2007, HSBC filed such a proof of claim with respect to the Taylors’ mortgage. To do so, it used the law firm Moss Codilis.[2] Moss retrieved the information on which the claim was based from HSBC’s computerized mortgage servicing database. No employee of HSBC reviewed the claim before filing.

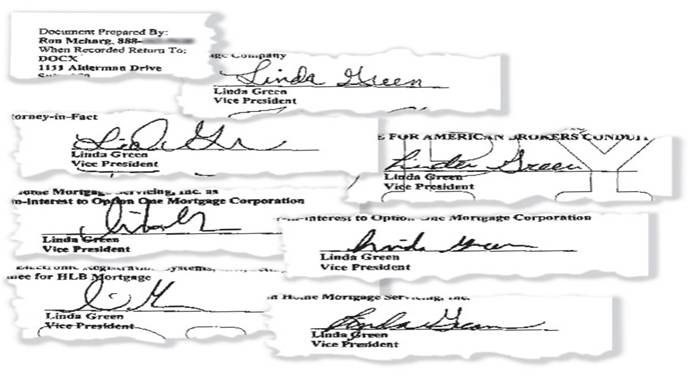

This proof of claim contained several errors: the amount of the Taylors’ monthly payment was incorrectly stated, the wrong mortgage note was attached, and the value of the home was understated by about $100,000. It is not clear whether the errors originated in HSBC’s database or whether they were introduced in Moss Codilis’s filing.[3]

2. The motion for relief from stay

At the time of the bankruptcy proceeding, the Taylors were also involved in a payment dispute with HSBC. HSBC believed the Taylors’ home to be in a flood zone and had obtained “forced insurance” for the property, the cost of which (approximately $180/month) it passed on to the Taylors. The Taylors disputed HSBC’s position and continued to pay their regular mortgage payment, without the additional insurance costs.[4] HSBC failed to acknowledge that the Taylors were making their regular payments and instead treated each payment as a partial payment, so that, in its records, the Taylors were becoming more delinquent each month.

Ordinarily, the filing of a bankruptcy petition imposes an automatic stay on all debt collection activities, including foreclosures. McCartney v. Integra Nat’l Bank North, 106 F.3d 506, 509 (3d Cir. 1997). However, pursuant to 11 U.S.C. § 362(d)(1), a secured creditor may file for relief from the stay “for cause, including the lack of adequate protection of an interest in property” of the creditor, in order to permit it to commence or continue foreclosure proceedings. Because of the Taylors’ withheld insurance payments, HSBC’s records indicated that they were delinquent. Thus, in January 2008, HSBC retained the Udren Firm to seek relief from the stay.

Mr. Udren is the only partner of the Udren Firm; Ms. Doyle, who appeared for the Udren Firm in the Taylors’ case, is a managing attorney at the firm, with twenty-seven years of experience. HSBC does not deign to communicate directly with the firms it employs in its high-volume foreclosure work; rather, it uses a computerized system called NewTrak (provided by a third party, LPS) to assign individual firms discrete assignments and provide the limited data the system deems relevant to each assignment.[5] The firms are selected and the instructions generated without any direct human involvement. The firms so chosen generally do not have the capacity to check the data (such as the amount of mortgage payment or time in arrears) provided to them by NewTrak and are not expected to communicate with other firms that may have done related work on the matter. Although it is technically possible for a firm hired through NewTrak to contact HSBC to discuss the matter on which it has been retained, it is clear from the record that this was discouraged and that some attorneys, including at least one Udren Firm attorney, did not believe it to be permitted.

In the Taylors’ case, NewTrak provided the Udren Firm with only the loan number, the Taylors’ name and address, payment amounts, late fees, and amounts past due. It did not provide any correspondence with the Taylors concerning the flood insurance dispute.

In January 2008, Doyle filed the motion for relief from the stay. This motion was prepared by non-attorney employees of the Udren Firm, relying exclusively on the information provided by NewTrak. The motion said that the debtor “has failed to discharge arrearages on said mortgage or has failed to make the current monthly payments on said mortgage since” the filing of the bankruptcy petition. (App. 65.) It identified “the failure to make . . . post-petition monthly payments” as stretching from November 1, 2007 to January 15, 2008, with an “amount per month” of $1455 (a monthly payment higher than that identified on the proof of claim filed earlier in the case by the Moss firm) and a total in arrears of $4367. (App. 66.) (It did note a “suspense balance” of $1040, which it subtracted from the ultimate total sought from the Taylors, but with no further explanation.) It stated that the Taylors had “inconsequential or no equity” in the property.[6] Id. The motion never mentioned the flood insurance dispute.

Doyle did nothing to verify the information in the motion for relief from stay besides check it against “screen prints” of the NewTrak information. She did not even access NewTrak herself. In effect, she simply proofread the document. It does not appear that NewTrak provided the Udren Firm with any information concerning the Taylors’ equity in their home, so Doyle could not have verified her statement in the motion concerning the lack of equity in any way, even against a “screen print.”

At the same time as it filed for relief from the stay, the Udren Firm also served the Taylors with a set of requests for admission (pursuant to Federal Rule of Bankruptcy Procedure 7036, incorporating Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 36) (“RFAs”). The RFAs sought formal and binding admissions that the Taylors had made no mortgage payments from November 2007 to January 2008 and that they had no equity in their home.

In February 2008, the Taylors filed a response to the motion for relief from stay, denying that they had failed to make payments and attaching copies of six checks tendered to HSBC during the relevant period. Four of them had already been cashed by HSBC.[7]

3. The claim objection and the response to the claim objection

In March 2008, the Taylors also filed an objection to HSBC’s proof of claim. The objection stated that HSBC had misstated the payment due on the mortgage and pointed out the dispute over the flood insurance. However, the Taylors did not respond to HSBC’s RFAs. Unless a party responds properly to a request for admission within 30 days, the “matter is [deemed] admitted.” Fed. R. Civ. P. 36(a)(3).

In the same month, Doyle filed a response to the objection to the proof of claim. The response did not discuss the flood insurance issue at all. However, it stated that “[a]ll figures contained in the proof of claim accurately reflect actual sums expended . . . by Mortgagee . . . and/or charges to which Mortgagee is contractually entitled and which the Debtors are contractually obligated to pay.” (App. 91.) This was indisputably incorrect, because the proof of claim listed an inaccurate monthly mortgage payment (which was also a different figure from the payment listed in Doyle’s own motion for relief from stay).

4. The claim hearings

In May 2008, the bankruptcy court held a hearing on both the motion for relief and the claim objection. HSBC was represented at the hearing by a junior associate at the Udren Firm, Mr. Fitzgibbon. At that hearing, Fitzgibbon ultimately admitted that, at the time the motion for relief from the stay was filed, HSBC had received a mortgage payment for November 2007, even though both the motion for stay and the response to the Taylors’ objection to the proof of claim stated otherwise.[8] Despite this, Fitzgibbon urged the court to grant the relief from stay, because the Taylors had not responded to HSBC’s RFAs (which included the “admission” that the Taylors had not made payments from November 2007 to January 2008). It appears from the record that Fitzgibbon initially sought to have the RFAs admitted as evidence even though he knew they contained falsehoods. (App. 101-102.)[9]

The bankruptcy court denied the request to enter the RFAs as evidence, noting that the firm “closed their eyes to the fact that there was evidence that . . . conflicted with the very admissions that they asked me [to deem admitted]. They. . . had that evidence [that the assertions in its motion were not accurate] in [their] possession and [they] went ahead like [they] never saw it.” (App. 108-109.) The court noted:

Maybe they have somebody there churning out these motions that doesn’t talk to the people that—you know, you never see the records, do you? Somebody sends it to you that sent it from somebody else.

(App. 109.) “I really find this motion to be in questionable good faith,” the court concluded. (App. 112.)

After the hearing, the bankruptcy court directed the Udren Firm to obtain an accounting from HSBC of the Taylors’ prepetition payments so that the arrearage on the mortgage could be determined correctly. At the next hearing, in June 2008, Fitzgibbon stated that he could not obtain an accounting from HSBC, though he had repeatedly placed requests via NewTrak. He told the court that he was literally unable to contact HSBC—his firm’s client—directly to verify information which his firm had already represented to the court that it believed to be true.

At the end of the June 2008 hearing, the court told Fitzgibbon: “I’m issuing an order to show cause on your firm, too, for filing these things . . . without having any knowledge. And filing answers . . . without any knowledge.” (App. 119.) Thereafter, the court entered an order sua sponte dated June 9, 2008, directing Fitzgibbon, Doyle, Udren, and others to appear and give testimony concerning the possibility of sanctions.

5. The sanctions hearings

The order stated that the purpose of the hearing included “to investigate the practices employed in this case by HSBC and its attorneys and agents and consider whether sanctions should issue against HSBC, its attorneys and agents.” (App 96-98.) Among those practices were “pressing a relief motion on admissions that were known to be untrue, and signing and filing pleadings without knowledge or inquiry regarding the matters pled therein.” Id. The order noted that “[t]he details are identified on the record of the hearings which are incorporated herein.” Id. In ordering Doyle to appear, the order noted that “the motion for relief, the admissions and the reply to the objection were prepared over Doyle’s name and signature.” Id. However, this order was not formally identified as “an order to show cause.”

The bankruptcy court held four hearings over several days, making in-depth inquiries into the communications between HSBC and its lawyers in this case, as well as the general capabilities and limitations of a system like NewTrak. Ultimately, it found that the following had violated Rule 9011: Fitzgibbon, for pressing the motion for relief based on claims he knew to be untrue; Doyle, for failing to make reasonable inquiry concerning the representations she made in the motion for relief from stay and the response to the claim objection; Udren and the Udren Firm itself, for the conduct of its attorneys; and HSBC, for practices which caused the failure to adhere to Rule 9011.

Because of his inexperience, the court did not sanction Fitzgibbon. However, it required Doyle to take 3 CLE credits in professional responsibility; Udren himself to be trained in the use of NewTrak and to spend a day observing his employees handling NewTrak; and both Doyle and Udren to conduct a training session for the firm’s relevant lawyers in the requirements of Rule 9011 and procedures for escalating inquiries on NewTrak. The court also required HSBC to send a copy of its opinion to all the law firms it uses in bankruptcy proceedings, along with a letter explaining that direct contact with HSBC concerning matters relating to HSBC’s case was permissible.[10]

B. The District Court’s Decision

Udren, Doyle, and the Udren Firm (but not HSBC) appealed the sanctions order to the District Court, which ultimately overturned the order. The District Court’s decision was based on three considerations: that the confusion in the case was attributable at least as much to the actions of Taylor’s counsel as to Doyle, Udren, and the Udren Firm; that the bankruptcy court seemed more concerned with “sending a message” to the bar concerning the use of computerized systems than with the conduct in the particular case; and that, since Udren himself did not sign any of the filings containing misrepresentations, he could not be sanctioned under Rule 9011. Although HSBC had not appealed, the District Court overturned the order with respect to HSBC, as well.

The United States trustee then appealed the District Court’s decision to this court.[11]

II.

Rule 9011 of the Federal Rules of Bankruptcy Procedure, the equivalent of Rule 11 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, requires that parties making representations to the court certify that “the allegations and other factual contentions have evidentiary support or, if specifically so identified, are likely to have evidentiary support.” Fed. R. Bank. P. 9011(b)(3).[12] A party must reach this conclusion based on “inquiry reasonable under the circumstances.” Fed. R. Bank. P. 9011(b). The concern of Rule 9011 is not the truth or falsity of the representation in itself, but rather whether the party making the representation reasonably believed it at the time to have evidentiary support. In determining whether a party has violated Rule 9011, the court need not find that a party who makes a false representation to the court acted in bad faith. “The imposition of Rule 11 sanctions . . . requires only a showing of objectively unreasonable conduct.” Fellheimer, Eichen & Braverman, P.C. v. Charter Tech., Inc., 57 F.3d 1215, 1225 (3d Cir. 1995). We apply an abuse of discretion standard in reviewing the decision of the bankruptcy court. See Cooter & Gell v. Hartmarx Corp., 496 U.S. 384, 405 (1990). However, we review its factual findings for clear error. Stern v. Marshall, ___ U.S. ___, 131 S. Ct. 2594, 2627 (2011) (Breyer, J., dissenting).

In this opinion, we focus on several statements by appellees: (1) in the motion for relief from stay, the statements suggesting that the Taylors had failed to make payments on their mortgage since the filing of their bankruptcy petition and the identification of the months in which and the amount by which they were supposedly delinquent; (2) in the motion for relief from stay, the statement that the Taylors had no or inconsequential equity in the property; (3) in the response to the claim objection, the statement that the figures in the proof of claim were accurate; and, (4) at the first hearing, the attempt to have the requests for admission concerning the lack of mortgage payments deemed admitted. As discussed above, all of these statements involved false or misleading representations to the court.[13]

A. Alleged literal truth

As an initial matter, the appellees’ insistence that Doyle’s and Fitzgibbon’s statements were “literally true” should not exculpate them from Rule 9011 sanctions. First, it should be noted that several of these claims were not, in fact, accurate. There was no literal truth to the statement in the request for relief from stay that the Taylors had no equity in their home. Doyle admitted that she made that statement simply as “part of the form pleading,” and “acknowledged having no knowledge of the value of the property and having made no inquiry on this subject.” (App. 215.) Similarly, the statement in the claim objection response that the figures in the original proof of claim were correct was false.

Just as importantly, appellees cite no authority, and we are aware of none, which permits statements under Rule 9011 that are literally true but actually misleading. If the reasonably foreseeable effect of Doyle’s or Fitzgibbon’s representations to the bankruptcy court was to mislead the court, they cannot be said to have complied with Rule 9011. See Williamson v. Recovery Ltd. P’ship, 542 F.3d 43, 51 (2d Cir. 2008) (a party violates Rule 11 “by making false, misleading, improper, or frivolous representations to the court”) (emphasis added).

In particular, even assuming that Doyle’s and Fitzgibbon’s statements as to the payments made by the Taylors were literally accurate, they were misleading. In attempting to evaluate whether HSBC was justified in seeking a relief from the stay on foreclosure, the court needed to know that at least partial payments had been made and that the failure to make some of the rest of the payments was due to a bona fide dispute over the amount due, not simple default. Instead, the court was told only that the Taylors had “failed to make regular mortgage payments” from November 1, 2007 to January 15, 2008, with a mysterious notation concerning a “suspense balance” following. (App. 214-15.) A court could only reasonably interpret this to mean that the Taylors simply had not made payments for the period specified. As the bankruptcy court found, “[f]or at best a $540 dispute, the Udren Firm mechanically prosecuted a motion averring a $4,367[] post-petition obligation, the aim of which was to allow HSBC to foreclose on [the Taylors’] house.” (App. 215.) Therefore, Doyle’s and Fitzgibbon’s statements in question were either false or misleading.

B. Reasonable inquiry

We must, therefore, determine the reasonableness of the appellees’ inquiry before they made their false representations. Reasonableness has been defined as “an objective knowledge or belief at the time of the filing of a challenged paper that the claim was well-grounded in law and fact.” Ford Motor Co. v. Summit Motor Prods., Inc., 930 F.2d 277, 289 (3d Cir. 1991) (internal quotations omitted). The requirement of reasonable inquiry protects not merely the court and adverse parties, but also the client. The client is not expected to know the technical details of the law and ought to be able to rely on his attorney to elicit from him the information necessary to handle his case in the most effective, yet legally appropriate, manner.

In determining reasonableness, we have sometimes looked at several factors: “the amount of time available to the signer for conducting the factual and legal investigation; the necessity for reliance on a client for the underlying factual information; the plausibility of the legal position advocated; .. . whether the case was referred to the signer by another member of the Bar . . . [; and] the complexity of the legal and factual issues implicated.” Mary Ann Pensiero, Inc. v. Lingle, 847 F.2d 90, 95 (3d Cir. 1988). However, it does not appear that the court must work mechanically through these factors when it considers whether to impose sanctions. Rather, it should consider the reasonableness of the inquiry under all the material circumstances. “[T]he applicable standard is one of reasonableness under the circumstances.” Bus. Guides, Inc. v. Chromatic Commc’ns Ents., Inc., 498 U.S. 533, 551 (1991); accord Garr v. U.S. Healthcare, Inc., 22 F.3d 1274, 1279 (3d Cir. 1994).

Central to this case, then, is the degree to which an attorney may reasonably rely on representations from her client. An attorney certainly “is not always foreclosed from relying on information from other persons.” Garr, 22 F.3d 1278. In making statements to the court, lawyers constantly and appropriately rely on information provided by their clients, especially when the facts are contained in a client’s computerized records. It is difficult to imagine how attorneys might function were they required to conduct an independent investigation of every factual representation made by a client before it could be included in a court filing. While Rule 9011 “does not recognize a `pure heart and empty head’ defense,” In re Cendant Corp. Derivative Action Litig., 96 F. Supp. 2d 403, 405 (D.N.J. 2000), a lawyer need not routinely assume the duplicity or gross incompetence of her client in order to meet the requirements of Rule 9011. It is therefore usually reasonable for a lawyer to rely on information provided by a client, especially where that information is superficially plausible and the client provides its own records which appear to confirm the information.

However, Doyle’s behavior was unreasonable, both as a matter of her general practice and in ways specific to this case. First, reasonable reliance on a client’s representations assumes a reasonable attempt at eliciting them by the attorney. That is, an attorney must, in her independent professional judgment, make a reasonable effort to determine what facts are likely to be relevant to a particular court filing and to seek those facts from the client. She cannot simply settle for the information her client determines in advance— by means of an automated system, no less—that she should be provided with.

Yet that is precisely what happened here. “[I]t appears,” the bankruptcy court observed, “that Doyle, the manager of the Udren Firm bankruptcy department, had no relationship with the client, HSBC.” (App. 202.) By working solely with NewTrak, a system which no one at the Udren Firm seems to have understood, much less had any influence over, Doyle permitted HSBC to define—perilously narrowly—the information she had about the Taylors’ matter. That HSBC was not providing her with adequate information through NewTrak should have been evident to Doyle from the face of the NewTrak file. She did not have any information concerning the Taylors’ equity in the home, though she made a statement specifically denying that they had any.

More generally, a reasonable attorney would not file a motion for relief from stay for cause without inquiring of the client whether it had any information relevant to the alleged cause, that is, the debtor’s failure to make payments. Had Doyle made even that most minimal of inquiries, HSBC presumably would have provided her with the information in its files concerning the flood insurance dispute, and Doyle could have included that information in her motion for relief from stay—or, perhaps, advised the client that seeking such a motion would be inappropriate under the circumstances.

With respect to the Taylors’ case in particular, Doyle ignored clear warning signs as to the accuracy of the data that she did receive. In responding to the motion for relief from stay, the Taylors submitted documentation indicating that they had already made at least partial payments for some of the months in question. In objecting to the proof of claim, the Taylors pointed out the inaccuracy of the mortgage payment listed and explained the circumstances surrounding the flood insurance dispute. Although Doyle certainly was not obliged to accept the Taylors’ claims at face value, they indisputably put her on notice that the matter was not as simple as it might have appeared from the NewTrak file. At that point, any reasonable attorney would have sought clarification and further documentation from her client, in order to correct any prior inadvertent misstatements to the court and to avoid any further errors. Instead, Doyle mechanically affirmed facts (the monthly mortgage payment) that her own prior filing with the court had already contradicted.

Doyle’s reliance on HSBC was particularly problematic because she was not, in fact, relying directly on HSBC. Instead, she relied on a computer system run by a third-party vendor. She did not know where the data provided by NewTrak came from. She had no capacity to check the data against the original documents if any of it seemed implausible. And she effectively could not question the data with HSBC. In her relationship with HSBC, Doyle essentially abdicated her professional judgment to a black box.

None of the other factors discussed in the Mary Ann Pensiero case which are applicable here affect our analysis of the reasonableness of appellees’ actions. This was not a matter of extreme complexity, nor of extraordinary deadline pressure. Although the initial data the Udren Firm received was not, in itself, wildly implausible, it was facially inadequate. In short, then, we find that Doyle’s inquiry before making her representations to the bankruptcy court was unreasonable.

In making this finding, we, of course, do not mean to suggest that the use of computerized databases is inherently inappropriate. However, the NewTrak system, as it was being used at the time of this case, permits parties at every level of the filing process to disclaim responsibility for inaccuracies. HSBC has handed off responsibility to a third-party maintainer, LPS, which, judging from the results in this case, has not generated particularly accurate records. LPS apparently regards itself as a mere conduit of information. Appellees, the attorneys and final link in the chain of transmission of this information to the court, claim reliance on NewTrak’s records. Who, precisely, can be held accountable if HSBC’s records are inadequately maintained, LPS transfers those records inaccurately into NewTrak, or a law firm relies on the NewTrak data without further investigation, thus leading to material misrepresentations to the court? It cannot be that all the parties involved can insulate themselves from responsibility by the use of such a system. In the end, we must hold responsible the attorneys who have certified to the court that the representations they are making are “well-grounded in law and fact.”

C. Notice

Doyle, Udren, and the Udren Firm also argue on appeal that they had insufficient notice that they were in danger of sanctions.[14] Rule 9011 directs that a court “[o]n its own initiative . . . may enter an order describing the specific conduct that appears to violate [the rule] and directing an attorney . . . to show cause why it has not violated [the rule].” Fed. R. Bank. P. 9011(c)(1)(B). Due process in the imposition of Rule 9011 sanctions requires “particularized notice.” Jones v. Pittsburgh Nat’l Corp., 899 F.2d 1350, 1357 (3d Cir. 1990). The meaning of “particularized notice” has not been rigorously defined in this circuit. In Fellheimer, we noted that this requirement was met where the sanctioned party “was provided with sufficient, advance notice of exactly which conduct was alleged to be sanctionable.” Fellheimer, 57 F.3d at 1225. In Simmerman v. Corino, 27 F.3d 58, 64 (3d Cir. 1994), we held that “the party sought to be sanctioned is entitled to particularized notice including, at a minimum, 1) the fact that Rule 11 sanctions are under consideration, 2) the reasons why sanctions are under consideration . . . .”

The bankruptcy court’s June order was clearly in substance an order to show cause, even if it was not specifically captioned as such. The more difficult question is whether the court adequately described “the specific conduct that appear[ed] to violate” Rule 9011, so as to give sufficient notice of “exactly which conduct was alleged to be sanctionable.” As mentioned above, the court’s June order identified “pressing a relief motion on admissions that were known to be untrue, and signing and filing pleadings without knowledge or inquiry regarding the matters pled therein” as the conduct the court wished to investigate. (App. 119) The judge also told Fitzgibbon, “I’m issuing an order to show cause on your firm, too, for filing these things . . . without having any knowledge. And filing answers . . . without any knowledge.” Id. The June order also made specific reference to “the motion for relief, the admissions and the reply to the objection.”

In these particular circumstances, the notice given to appellees was sufficient to put them on notice as to which aspects of their conduct were considered sanctionable. At that point in the case, the Udren Firm lawyers had only filed three substantive papers with the court—totaling six (substantive) pages—and the court found all of them problematic. Appellees’ claim that they believed that the only issue at the time of the hearing was Fitzgibbon’s inability to contact HSBC is simply not plausible in light of the language of the June order and the bankruptcy court’s statements at the hearing, which were incorporated by reference into the June order. In a case in which more extensive docket activity had taken place, the bankruptcy court’s order might not have been sufficient to inform appellees as to which of their filings were sanctionable, but, given the unusual circumstances here, it was. But see Martens v. Thomann, 273 F.3d 159, 178 (2d Cir. 2001) (requiring specific identification of individual challenged statements to uphold imposition of sanctions).

D. The Udren Firm and Udren’s individual liability

We also find that it was appropriate to extend sanctions to the Udren Firm itself. Rule 11 explicitly allows the imposition of sanctions against law firms. Fellheimer, 57 F.3d 1215 at 1223 n.5. In this instance, the bankruptcy court found that the misrepresentations in the case arose not simply from the irresponsibility of individual attorneys, but from the system put in place at the Udren Firm, which emphasized high-volume, high-speed processing of foreclosures to such an extent that it led to violations of Rule 9011.

However, we do not find that responsibility for these failures extends specifically to Udren, whose involvement in this matter was limited to his role as sole shareholder of the firm.

E. The District Court’s reversal of sanctions against HSBC

Ordinarily, of course, a party which does not appeal a decision by a district court cannot receive relief with respect to that decision. “[T]he mere fact that a [party] may wind up with a judgment against one [party] that is not logically consistent with an unappealed judgment against another is not alone sufficient to justify taking away the unappealed judgment in favor of a party not before the court.” Repola v. Morbark Indus., Inc., 980 F.2d 938, 942 (3d Cir. 1992). However, “where the disposition as to one party is inextricably intertwined with the interests of a non-appealing party,” it may be “impossible to grant relief to one party without granting relief to the other.” United States v. Tabor Court Realty Corp., 943 F.2d 335, 344 (3d Cir. 1991). In Tabor Court Realty, a contract dispute, the assignee of a property had failed to appeal a decision, while the assignor had (and had ultimately prevailed). Given that the dispute was over the disposition of the property, it was impossible to grant relief to the assignor without also granting relief to the assignee.

In this instance, whether the lawyers at the Udren Firm violated Rule 9011 is a question analytically distinct from whether HSBC was responsible for any violations of Rule 9011. A court might find that HSBC was responsible for violations, whereas, say, Udren himself was not. It was entirely possible for HSBC to comply with the sanctions ordered (a letter to its firms informing them that they are permitted to consult with HSBC) without affecting the interests of the lawyers at the Udren Firm. Therefore, the interests of the lawyers at the Udren Firm and HSBC were not “inextricably intertwined,” and the District Court lacked jurisdiction to reverse the sanctions against HSBC.

F. Alternative basis for the District Court’s decision

In reversing the bankruptcy court’s decision, the District Court focused on that court’s apparent attention to the broader problems of high-volume bankruptcy practice in imposing sanctions. It is true that the bankruptcy judge noted that appellees were not the first attorneys to run into these sorts of difficulties in her court. But she nonetheless made individualized findings of wrong-doing after four days of hearings and issued sanctions thoughtfully chosen to prevent the recurrence of problems at the Udren Firm based on what she had learned of practices there. Insofar as she considered the effect of the sanctions on the future conduct of other attorneys appearing before her, such considerations were permissible. After all, “the prime goal [of Rule 11 sanctions] should be deterrence of repetition of improper conduct.” Waltz v. County of Lycoming, 974 F.2d 387, 390 (3d Cir. 1992).

G. Conclusion

We appreciate that the use of technology can save both litigants and attorneys time and money, and we do not, of course, mean to suggest that the use of databases or even certain automated communications between counsel and client are presumptively unreasonable. However, Rule 11 requires more than a rubber-stamping of the results of an automated process by a person who happens to be a lawyer. Where a lawyer systematically fails to take any responsibility for seeking adequate information from her client, makes representations without any factual basis because they are included in a “form pleading” she has been trained to fill out, and ignores obvious indications that her information may be incorrect, she cannot be said to have made reasonable inquiry. Therefore, we find that the bankruptcy court did not abuse its discretion in imposing sanctions on Doyle or the Udren Firm itself. However, it did abuse its discretion in imposing sanctions on Udren individually.

III.

For the foregoing reasons, we will reverse the District Court with respect to Doyle and the Udren Firm, affirming the bankruptcy court’s imposition of sanctions. With respect to HSBC, as discussed previously, the District Court lacked jurisdiction to reverse the sanctions, as do we; therefore, we vacate the District Court’s order with respect to that party, leaving the sanctions imposed by the bankruptcy court in place. We will affirm the District Court with respect to Udren individually, reversing the bankruptcy’s court imposition of sanctions.

[1] Although HSBC was sanctioned by the bankruptcy court, it did not participate in this appeal.

[2] Moss Codilis is not involved in the present appeal. However, it is worth noting that the firm has come under serious judicial criticism for its lax practices in bankruptcy proceedings. “In total, [the court knows] of 23 instances in which [Moss Codilis] has violated [court rules] in this District alone.” In re Greco, 405 B.R. 393, 394 (Bankr. S.D. Fla. 2009); see also In re Waring, 401 B.R. 906 (Bankr. N.D. Ohio 2009).

[3] HSBC ultimately corrected these errors in an amended court filing.

[4] This dispute has now been resolved in favor of the Taylors. (App. 199.)

[5] LPS is also not involved in the present appeal, as the bankruptcy court found that it had not engaged in wrongdoing in this case. However, both the accuracy of its data and the ethics of its practices have been repeatedly called into question elsewhere. See, e.g., In re Wilson, 2011 WL 1337240 at *9 (Bankr. E.D.La. Apr. 7, 2011) (imposing sanctions after finding that LPS had issued “sham” affidavits and perpetrated fraud on the court); In re Thorne, 2011 WL 2470114 (Bankr. N.D. Miss. June 16, 2011); In re Doble, 2011 WL 1465559 (Bankr. S.D. Cal. Apr. 14, 2011).

[6] The U.S. Trustee now points out that the motion also claimed that the Taylors were not making payments to other creditors under their bankruptcy plan and argues that this claim was false as well. Since the bankruptcy court did not make any findings with respect to this issue, we will not consider it.

[7] It is not clear from the briefing whether the last two checks, for February and March 2008, had actually been submitted to HSBC at the time the motion was filed; appellees deny that they were. However, appellees do not dispute that checks for October and November 2007 and January 2008 had been cashed.

[8] Appellees concede that, by the time the May hearing was held, HSBC had received all of the relevant checks.

[9] Appellees now claim that “[i]t is clear from the record, that Mr. Fitzgibbon honestly disclosed to the Court that these checks had just been received by [the] Udren [Firm] and that the only issue was that of flood insurance.” (App’ee Br. 16.) However, this disclosure did not occur until after Fitzgibbon had attempted to enter the RFAs, which made contrary claims, as evidence, and debtor’s counsel raised the issue. As the bankruptcy court described it, “[Fitzgibbon] first argued that I should rule in HSBC’s favor . . . On probing by the court, he acknowledged that as of the date of the continued hearing, he had learned that [the Taylors] had made every payment.” (App. 196, emphasis added.) In a Rule 9011/11 proceeding such as the present one, one would expect the challenged parties to be scrupulously careful in their representations to the court.

[10] Taylor’s counsel was also ultimately sanctioned and removed from the case. Counsel did not perform competently, as is evidenced by the Taylors’ failure to contest HSBC’s RFAs. She also made a number of inaccurate statements in her representations to the court. However, it is clear that her conduct did not induce the misrepresentations by HSBC or its attorneys. As the bankruptcy court correctly noted, “the process employed by a mortgagee and its counsel must be fair and transparent without regard to the quality of debtor’s counsel since many debtors are unrepresented and cannot rely on counsel to protect them.” (App. 214.)

[11] The bankruptcy court had jurisdiction under 28 U.S.C. § 157(a). The District Court had jurisdiction under 28 U.S.C. § 158(a)(1), except as discussed below. We have jurisdiction under 28 U.S.C. § 158(d).

[12] “[C]ases decided pursuant to [Fed. R. Civ. P. 11] apply to Rule 9011.” In re Gioioso, 979 F.2d 956, 960 (3d Cir. 1992).

[13] Appellees expend great energy in questioning the factual findings of the bankruptcy court, but we, like the District Court before us, see no error.

[14] Any claim regarding a due process right to notification of the form of sanctions being considered has been waived by appellees, as it was not raised in their papers, either here or in the district court. United States v. Pelullo, 399 F.3d 197, 222 (3d Cir. 2005).

[ipaper docId=63127059 access_key=key-2ki51goybcvd7k5rv5hl height=600 width=600 /]

© 2010-19 FORECLOSURE FRAUD | by DinSFLA. All rights reserved.

Recent Comments