INTRODUCTION

Before Washington Mutual Bank, FA (WaMu) was seized by federal banking regulators in 2008, it made many residential real estate loans and used those loans as collateral for mortgage-backed securities.1

Many of the loans went into default, which led to nonjudicial foreclosure proceedings.

Some of the foreclosures generated lawsuits, which raised a wide variety of claims.

The allegations that the instant case shares with some of the other lawsuits are that

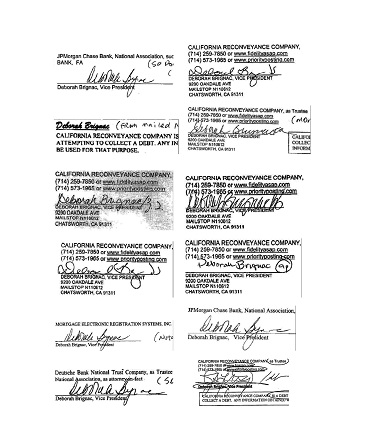

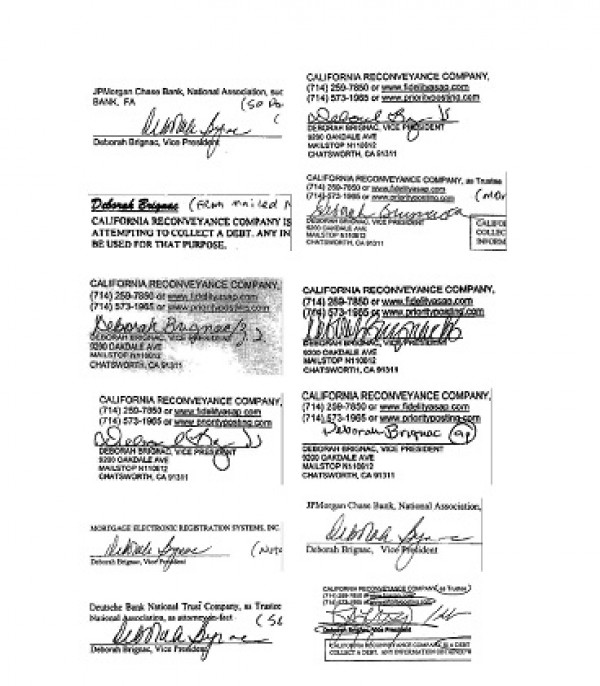

(1) documents related to the foreclosure contained forged signatures of Deborah Brignac and (2) the foreclosing entity was not the true owner of the loan because its chain of ownership had been broken by a defective transfer of the loan to the securitized trust established for the mortgage-backed securities. Here, the specific defect alleged is that the attempted transfers were made after the closing date of the securitized trust holding the pooled mortgages and therefore the transfers were ineffective.

In this appeal, the borrower contends the trial court erred by sustaining defendants’ demurrer as to all of his causes of action attacking the nonjudicial foreclosure. We conclude that, although the borrower’s allegations are somewhat confusing and may contain contradictions, he nonetheless has stated a wrongful 2

foreclosure claim under the lenient standards applied to demurrers. We conclude that a borrower may challenge the securitized trust’s chain of ownership by alleging the attempts to transfer the deed of trust to the securitized trust (which was formed under New York law) occurred after the trust’s closing date. Transfers that violate the terms of the trust instrument are void under New York trust law, and borrowers have standing to challenge void assignments of their loans even though they are not a party to, or a third party beneficiary of, the assignment agreement.

H. Causes of Action Stated Based on the foregoing, we conclude that Glaski’s fourth cause of action has stated a claim for wrongful foreclosure. It follows that Glaski also has stated claims for quiet title (third cause of action), declaratory relief (fifth cause of action), cancellation of instruments (eighth cause of action), and unfair business practices under Business and Professions Code section 17200 (ninth cause of action).

We therefore reverse the judgment of dismissal and remand for further proceedings.

THOMAS A. GLASKI, Plaintiff and Appellant,

v.

BANK OF AMERICA, NATIONAL ASSOCIATION et al. Defendants and Respondents.

AlvaradoSmith, Theodore E. Bacon, and Mikel A. Glavinovich, for Defendants and Respondents.

CERTIFIED FOR PUBLICATION

OPINION

FRANSON, J.

INTRODUCTION

Before Washington Mutual Bank, FA (WaMu) was seized by federal banking regulators in 2008, it made many residential real estate loans and used those loans as collateral for mortgage-backed securities.[1] Many of the loans went into default, which led to nonjudicial foreclosure proceedings. Some of the foreclosures generated lawsuits, which raised a wide variety of claims. The allegations that the instant case shares with some of the other lawsuits are that (1) documents related to the foreclosure contained forged signatures of Deborah Brignac and (2) the foreclosing entity was not the true owner of the loan because its chain of ownership had been broken by a defective transfer of the loan to the securitized trust established for the mortgage-backed securities. Here, the specific defect alleged is that the attempted transfers were made after the closing date of the securitized trust holding the pooled mortgages and therefore the transfers were ineffective.

In this appeal, the borrower contends the trial court erred by sustaining defendants’ demurrer as to all of his causes of action attacking the nonjudicial foreclosure. We conclude that, although the borrower’s allegations are somewhat confusing and may contain contradictions, he nonetheless has stated a wrongful foreclosure claim under the lenient standards applied to demurrers. We conclude that a borrower may challenge the securitized trust’s chain of ownership by alleging the attempts to transfer the deed of trust to the securitized trust (which was formed under New York law) occurred after the trust’s closing date. Transfers that violate the terms of the trust instrument are void under New York trust law, and borrowers have standing to challenge void assignments of their loans even though they are not a party to, or a third party beneficiary of, the assignment agreement.

We therefore reverse the judgment of dismissal and remand for further proceedings.

FACTS

The Loan

Thomas A. Glaski, a resident of Fresno County, is the plaintiff and appellant in this lawsuit. The operative second amended complaint (SAC) alleges the following: In July 2005, Glaski purchased a home in Fresno for $812,000 (the Property). To finance the purchase, Glaski obtained a $650,000 loan from WaMu. Initial monthly payments were approximately $1,700. Glaski executed a promissory note and a deed of trust that granted WaMu a security interest in the Property (the Glaski deed of trust). Both documents were dated July 6, 2005. The Glaski deed of trust identified WaMu as the lender and the beneficiary, defendant California Reconveyance Company (California Reconveyance) as the trustee, and Glaski as the borrower.

Paragraph 20 of the Glaski deed of trust contained the traditional terms of a deed of trust and states that the note, together with the deed of trust, can be sold one or more times without prior notice to the borrower. In this case, a number of transfers purportedly occurred. The validity of attempts to transfer Glaski’s note and deed of trust to a securitized trust is a fundamental issue in this appeal.

Paragraph 22—another provision typical of deeds of trust—sets forth the remedies available to the lender in the event of a default. Those remedies include (1) the lender’s right to accelerate the debt after notice to the borrower and (2) the lender’s right to “invoke the power of sale” after the borrower has been given written notice of default and of the lender’s election to cause the property to be sold. Thus, under the Glaski deed of trust, it is the lender-beneficiary who decides whether to pursue nonjudicial foreclosure in the event of an uncured default by the borrower. The trustee implements the lender-beneficiary’s decision by conducting the nonjudicial foreclosure.[2]

Glaski’s loan had an adjustable interest rate, which caused his monthly loan payment to increase to $1,900 in August 2006 and to $2,100 in August 2007. In August 2008, Glaski attempted to work with WaMu’s loan modification department to obtain a modification of the loan. There is no dispute that Glaski defaulted on the loan by failing to make the monthly installment payments.

Creation of the WaMu Securitized Trust

In late 2005, the WaMu Mortgage Pass-Through Certificates Series 2005-AR17 Trust was formed as a common law trust (WaMu Securitized Trust) under New York law. The corpus of the trust consists of a pool of residential mortgage notes purportedly secured by liens on residential real estate. La Salle Bank, N.A., was the original trustee for the WaMu Securitized Trust.[3] Glaski alleges that the WaMu Securitized Trust has no continuing duties other than to hold assets and to issue various series of certificates of investment. A description of the certificates of investment as well as the categories of mortgage loans is included in the prospectus filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) on October 21, 2005. Glaski alleges that the investment certificates issued by the WaMu Securitized Trust were duly registered with the SEC.

The closing date for the WaMu Securitized Trust was December 21, 2005, or 90 days thereafter. Glaski alleges that the attempt to assign his note and deed of trust to the WaMu Securitized Trust was made after the closing date and, therefore, the assignment was ineffective. (See fn. 12, post.)

WaMu’s Failure and Transfers of the Loan

In September 2008, WaMu was seized by the Office of Thrift Supervision and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) was appointed as a receiver for WaMu. That same day, the FDIC, in its capacity as receiver, sold the assets and liabilities of WaMu to defendant JPMorgan Chase Bank, N.A., (JP Morgan). This transaction was documented by a “PURCHASE AND ASSUMPTION AGREEMENT WHOLE BANK” (boldface and underlining omitted) between the FDIC and JP Morgan dated as of September 25, 2008. If Glaski’s loan was not validly transferred to the WaMu Securitized Trust, it is possible, though not certain, that JP Morgan acquired the Glaski deed of trust when it purchased WaMu assets from the FDIC.[4] JP Morgan also might have acquired the right to service the loans held by the WaMu Securitized Trust.

In September 2008, Glaski spoke to a representative of defendant Chase Home Finance LLC (Chase),[5] which he believed was an agent of JP Morgan, and made an oral agreement to start the loan modification process. Glaski believed that Chase had taken over loan modification negotiations from WaMu.

On December 9, 2008, two documents related to the Glaski deed of trust were recorded with the Fresno County Recorder: (1) an “ASSIGNMENT OF DEED OF TRUST” and (2) a “NOTICE OF DEFAULT AND ELECTION TO SELL UNDER DEED OF TRUST” (boldface omitted; hereinafter the NOD). The assignment stated that JP Morgan transferred and assigned all beneficial interest under the Glaski deed of trust to “LaSalle Bank NA as trustee for WaMu [Securitized Trust]” together with the note described in and secured by the Glaski deed of trust.[6]

Notice of Default and Sale of the Property

The NOD informed Glaski that (1) the Property was in foreclosure because he was behind in his payments[7] and (2) the Property could be sold without any court action. The NOD also stated that “the present beneficiary under” the Glaski deed of trust had delivered to the trustee a written declaration and demand for sale. According to the NOD, all sums secured by the deed of trust had been declared immediately due and payable and that the beneficiary elected to cause the Property to be sold to satisfy that obligation.

The NOD stated the amount of past due payments was $11,200.78 as of December 8, 2008.[8] It also stated: “To find out the amount you must pay, or to arrange for payment to stop the foreclosure, … contact: JPMorgan Chase Bank, National Association, at 7301 BAYMEADOWS WAY, JACKSONVILLE, FL 32256, (877) 926-8937.”

Approximately three months after the NOD was recorded and served, the next official step in the nonjudicial foreclosure process occurred. On March 12, 2009, a “NOTICE OF TRUSTEE’S SALE” was recorded by the Fresno County Recorder (notice of sale). The sale was scheduled for April 1, 2009. The notice stated that Glaski was in default under his deed of trust and estimated the amount owed at $734,115.10.

The notice of sale indicated it was signed on March 10, 2009, by Deborah Brignac, as Vice President for California Reconveyance. Glaski alleges that Brignac’s signature was forged to effectuate a fraudulent foreclosure and trustee’s sale of his primary residence.

Glaski alleges that from March until May 2009, he was led to believe by his negotiations with Chase that a loan modification was in process with JP Morgan.

Despite these negotiations, a nonjudicial foreclosure sale of the Property was conducted on May 27, 2009. Bank of America, as successor trustee for the WaMu Securitized Trust and beneficiary under the Glaski deed of trust, was the highest bidder at the sale.

On June 15, 2009, another “ASSIGNMENT OF DEED OF TRUST” was recorded with the Fresno County Recorder. This assignment, like the assignment recorded in December 2008, identified JP Morgan as the assigning party. The entity receiving all beneficial interest under the Glaski deed of trust was identified as Bank of America, “as successor by merger to `LaSalle Bank NA as trustee for WaMu [Securitized Trust]. …”[9] The assignment of deed of trust indicates it was signed by Brignac, as Vice President for JP Morgan. Glaski alleges that Brignac’s signature was forged.

The very next document filed by the Fresno County Recorder on June 15, 2009, was a “TRUSTEE’S DEED UPON SALE.” (Boldface omitted.) The trustee’s deed upon sale stated that California Reconveyance, as the duly appointed trustee under the Glaski deed of trust, granted and conveyed to Bank of America, as successor by merger to La Salle NA as trustee for the WaMu Securitized Trust, all of its right, title and interest to the Property. The trustee’s deed upon sale stated that the amount of the unpaid debt and costs was $738,238.04 and that the grantee, paid $339,150 at the trustee’s sale, either in lawful money or by credit bid.

PROCEEDINGS

In October 2009, Glaski filed his original complaint. In August 2011, Glaski filed the SAC, which alleged the following numbered causes of action:

(1) Fraud against JPMorgan and California Reconveyance for the alleged forged signatures of Deborah Brignac as vice president for California Reconveyance and then as vice president of JPMorgan;

(2) Fraud against all defendants for their failure to timely and properly transfer the Glaski loan to the WaMu Securitized Trust and their representations to the contrary;

(3) Quiet title against Bank of America, Chase, and California Reconveyance based on the broken chain of title caused by the defective transfer of the loan to the WaMu Securitized Trust;

(4) Wrongful foreclosure against all defendants, based on the forged signatures of Deborah Brignac and the failure to timely and properly transfer the Glaski loan to the WaMu Securitized Trust;

(5) Declaratory relief against all defendants, based on the above acts by defendants;

(8) Cancellation of various foreclosure documents against all defendants, based on the above acts by the defendants; and

(9) Unfair practices under California Business and Professions Code section 17200, et seq., against all defendants.

Among other things, Glaski raised questions regarding the chain of ownership, by contending that the defendants were not the lender or beneficiary under his deed of trust and, therefore, did not have the authority to foreclose.

In September 2011, defendants filed a demurrer that challenged each cause of action in the SAC on the grounds that it failed to state facts sufficient to constitute a claim for relief. With respect to the wrongful foreclosure cause of action, defendants argued that Glaski failed to allege (1) any procedural irregularity that would justify setting aside the presumptively valid trustee’s sale and (2) that he could tender the amount owed if the trustee’s sale were set aside.

To support their demurrer to the SAC, defendants filed a request for judicial notice concerning (1) Order No. 2008-36 of the Office of Thrift Supervision, dated September 25, 2008, appointing the FDIC as receiver of Washington Mutual Bank and (2) the Purchase and Assumption Agreement Whole Bank between the FDIC and JP Morgan dated as of September 25, 2008, concerning the assets, deposits and liabilities of Washington Mutual Bank.[10]

Glaski opposed the demurrer, arguing that breaks in the chain of ownership of his deed of trust were sufficiently alleged. He asserted that Brignac’s signature was forged and the assignment bearing that forgery was void. His opposition also provided a more detailed explanation of his argument that his deed of trust had not been effectively transferred to the WaMu Securitized Trust that held the pool of mortgage loans. Thus, in Glaski’s view, Bank of America’s claim as the successor trustee is flawed because the trust never held his loan.

On November 15, 2011, the trial court heard argument from counsel regarding the demurrer. Counsel for Glaski argued, among other things, that the possible ratification of the allegedly forged signatures of Brignac presented an issue of fact that could not be resolved at the pleading stage.

Later that day, the court filed a minute order adopting its tentative ruling. As background for the issues presented in this appeal, we will describe the trial court’s ruling on Glaski’s two fraud causes of action and his wrongful foreclosure cause of action.

The ruling stated that the first cause of action for fraud was based on an allegation that defendants misrepresented material information by causing a forged signature to be placed on the June 2009 assignment of deed of trust. The ruling stated that if the signature of Brignac was forged, California Reconveyance “ratified the signature by treating it as valid.” As an additional rationale, the ruling cited Gomes v. Countrywide Home Loans, Inc. (2011) 192 Cal.App.4th 1149 (Gomes) for the proposition that the exhaustive nature of California’s nonjudicial foreclosure scheme prohibited the introduction of additional requirements challenging the authority of the lender’s nominee to initiate nonjudicial foreclosure.

As to the second cause of action for fraud, the ruling noted the allegation that the Glaski deed of trust was transferred to the WaMu Securitized Trust after the trust’s closing date and summarized the claim as asserting that the Glaski deed of trust had been improperly transferred and, therefore, the assignment was void ab initio. The ruling rejected this claim, stating: “[T]o reiterate, Gomes v. Countrywide, supra holds that there is no legal basis to challenge the authority of the trustee, mortgagee, beneficiary, or any of their authorized agents to initiate the foreclosure process citing Civil Code § 2924, subd. (a)(1).”

The ruling stated that the fourth cause of action for wrongful foreclosure was “based upon the invalidity of the foreclosure sale conducted on May 27, 2009 due to the `forged’ signature of Deborah Brignac and the failure of Defendants to `provide a chain of title of the note and the mortgage.'” The ruling stated that, as explained earlier, “these contentions are meritless” and sustained the general demurrer to the wrongful foreclosure claim without leave to amend.

Subsequently, a judgment of dismissal was entered and Glaski filed a notice of appeal.

DISCUSSION

I. STANDARD OF REVIEW

The trial court sustained the demurrer to the SAC on the ground that it did “not state facts sufficient to constitute a cause of action.” (Code Civ. Proc., § 430.10, subd. (e).) The standard of review applicable to such an order is well settled. “[W]e examine the complaint de novo to determine whether it alleges facts sufficient to state a cause of action under any legal theory. …” (McCall v. PacifiCare of Cal., Inc. (2001) 25 Cal.4th 412, 415.)

When conducting this de novo review, “[w]e give the complaint a reasonable interpretation, reading it as a whole and its parts in their context. [Citation.] Further, we treat the demurrer as admitting all material facts properly pleaded, but do not assume the truth of contentions, deductions or conclusions of law. [Citations.]” (City of Dinuba v. County of Tulare (2007) 41 Cal.4th 859, 865.) Our consideration of the facts alleged includes “those evidentiary facts found in recitals of exhibits attached to a complaint.” (Satten v. Webb (2002) 99 Cal.App.4th 365, 375.) “We also consider matters which may be judicially noticed.” (Serrano v. Priest (1971) 5 Cal.3d 584, 591; see Code Civ. Proc., § 430.30, subd. (a) [use of judicial notice with demurrer].) Courts can take judicial notice of the existence, content and authenticity of public records and other specified documents, but do not take judicial notice of the truth of the factual matters asserted in those documents. (Mangini v. R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co. (1994) 7 Cal.4th 1057, 1063, overruled on other grounds in In re Tobacco Cases II (2007) 41 Cal.4th 1257, 1262.) We note “in passing upon the question of the sufficiency or insufficiency of a complaint to state a cause of action, it is wholly beyond the scope of the inquiry to ascertain whether the facts stated are true or untrue” as “[t]hat is always the ultimate question to be determined by the evidence upon a trial of the questions of fact.” (Colm v. Francis (1916) 30 Cal.App. 742, 752.))

II. FRAUD

A. Rules for Pleading Fraud

The elements of a fraud cause of action are (1) misrepresentation, (2) knowledge of the falsity or scienter, (3) intent to defraud—that is, induce reliance, (4) justifiable reliance, and (5) resulting damages. (Lazar v. Superior Court (1996) 12 Cal.4th 631, 638.) These elements may not be pleaded in a general or conclusory fashion. (Id. at p. 645.) Fraud must be pled specifically—that is, a plaintiff must plead facts that show with particularity the elements of the cause of action. (Ibid.)

In their demurrer, defendants contended facts establishing detrimental reliance were not alleged.

B. First Cause of Action for Fraud, Lack of Specific Allegations of Reliance

Glaski’s first cause of action, which alleges a fraud implemented through forged documents, alleges that defendants’ act “caused Plaintiff to rely on the recorded documents and ultimately lose the property which served as his primary residence, and caused Plaintiff further damage, proof of which will be made at trial.”

This allegation is a general allegation of reliance and damage. It does not identify the particular acts Glaski took because of the alleged forgeries. Similarly, it does not identify any acts that Glaski did not take because of his reliance on the alleged forgeries. Therefore, we conclude that Glaski’s conclusory allegation of reliance is insufficient under the rules of law that require fraud to be pled specifically. (Lazar v. Superior Court, supra, 12 Cal.4th at p. 645.)

The next question is whether the trial court abused its discretion in sustaining the demurrer to the first fraud cause of action without leave to amend.

In March 2011, the trial court granted Glaski leave to amend when ruling on defendants’ motion for judgment on the pleadings. The court indicated that Glaski’s complaint had jumbled together many different statutes and theories of liability and directed Glaski to avoid “chain letter” allegations in his amended pleading.

Glaski’s first amended complaint set forth two fraud causes of action that are similar to those included in the SAC.

Defendants demurred to the first amended complaint. The trial court’s minute order states: “Plaintiff is advised for the last time to plead each cause of action such that only the essential elements for the claim are set forth without reincorporation of lengthy `general allegations’. In other words, the `facts’ to be pleaded are those upon which liability depends (i.e., `the facts constituting the cause of action’).”

After Glaski filed his SAC, defendants filed a demurrer. Glaski then filed an opposition that asserted he had properly alleged detrimental reliance. He did not argue he could amend to allege specifically the action he took or did not take because of his reliance on the alleged forgeries.

Accordingly, Glaski failed to carry his burden of demonstrating he could allege with the requisite specificity the elements of justifiable reliance and damages resulting from that reliance. (See Blank v. Kirwan (1985) 39 Cal.3d 311, 318 [the burden of articulating how a defective pleading could be cured is squarely on the plaintiff].) Therefore, we conclude that the trial court did not abuse its discretion when it denied leave to amend as to the SAC’s first cause of action for fraud.

C. Second Fraud Cause of Action, Lack of Specific Allegations of Reliance

Glaski’s second cause of action for fraud alleged that WaMu failed to transfer his note and deed of trust into the WaMu Securitized Trust back in 2005. Glaski further alleged, in essence, that defendants attempted to rectify WaMu’s failure by engaging in a fraudulent scheme to assign his note and deed of trust into the WaMu Securitized Trust. The scheme was implemented in 2008 and 2009 and its purpose was to enable defendants to fraudulently foreclosure against the Property.

The second cause of action for fraud attempts to allege detrimental reliance in the following sentence: “Defendants, and each of them, also knew that the act of recording the Assignment of Deed of trust without the authorization to do so would cause Plaintiff to rely upon Defendants’ actions by attempting to negotiate a loan modification with representatives of Chase Home Finance, LLC, agents of JP MORGAN.” The assignment mentioned in this allegation is the assignment of deed of trust recorded in June 2009—no other assignment of deed of trust is referred to in the second cause of action.

The allegation of reliance does not withstand scrutiny. The act of recording the allegedly fraudulent assignment occurred in June 2009, after the trustee’s sale of the Property had been conducted. If Glaski was induced to negotiate a loan modification at that time, it is unclear how negotiations occurring after the May 2009 trustee’s sale could have diverted him from stopping the trustee’s sale. Thus, Glaski’s allegation of reliance is not connected to any detriment or damage.

Because Glaski has not demonstrated how this defect in his fraud allegations could be cured by amendment, we conclude that the trial court did not abuse its discretion in denying leave to amend the second cause of action in the SAC.

III. WRONGFUL FORECLOSURE BY NONHOLDER OF THE DEED OF TRUST

A. Glaski’s Theory of Wrongful Foreclosure

Glaski’s theory that the foreclosure was wrongful is based on (1) the position that paragraph 22 of the Glaski deed of trust authorizes only the lender-beneficiary (or its assignee) to (a) accelerate the loan after a default and (b) elect to cause the Property to be sold and (2) the allegation that a nonholder of the deed of trust, rather than the true beneficiary, instructed California Reconveyance to initiate the foreclosure.[11]

In particular, Glaski alleges that (1) the corpus of the WaMu Securitized Trust was a pool of residential mortgage notes purportedly secured by liens on residential real estate; (2) section 2.05 of “the Pooling and Servicing Agreement” required that all mortgage files transferred to the WaMu Securitized Trust be delivered to the trustee or initial custodian of the WaMu Securitized Trust before the closing date of the trust (which was allegedly set for December 21, 2005, or 90 days thereafter); (3) the trustee or initial custodian was required to identify all such records as being held by or on behalf of the WaMu Securitized Trust; (4) Glaski’s note and loan were not transferred to the WaMu Securitized Trust prior to its closing date; (5) the assignment of the Glaski deed of trust did not occur by the closing date in December 2005; (6) the transfer to the trust attempted by the assignment of deed of trust recorded on June 15, 2009, occurred long after the trust was closed; and (7) the attempted assignment was ineffective as the WaMu Securitized Trust could not have accepted the Glaski deed of trust after the closing date because of the pooling and servicing agreement and the statutory requirements applicable to a Real Estate Mortgage Investment Conduit (REMIC) trust.[12]

B. Wrongful Foreclosure by a Nonholder of the Deed of Trust

The theory that a foreclosure was wrongful because it was initiated by a nonholder of the deed of trust has also been phrased as (1) the foreclosing party lacking standing to foreclose or (2) the chain of title relied upon by the foreclosing party containing breaks or defects. (See Scott v. JPMorgan Chase Bank, N.A. (2013) 214 Cal.App.4th 743, 764; Herrera v. Deutsche Bank National Trust Co., supra, 196 Cal.App.4th 1366 [Deutsche Bank not entitled to summary judgment on wrongful foreclosure claim because it failed to show a chain of ownership that would establish it was the true beneficiary under the deed of trust]; Guerroro v. Greenpoint Mortgage Funding, Inc. (9th Cir. 2010) 403 Fed.Appx. 154, 156 [rejecting a wrongful foreclosure claim because, among other things, plaintiffs “have not pleaded any facts to rebut the unbroken chain of title”].)

In Barrionuevo v. Chase Bank, N.A. (N.D.Cal. 2012) 885 F.Supp.2d 964, the district court stated: “Several courts have recognized the existence of a valid cause of action for wrongful foreclosure where a party alleged not to be the true beneficiary instructs the trustee to file a Notice of Default and initiate nonjudicial foreclosure.” (Id. at p. 973.) We agree with this statement of law, but believe that properly alleging a cause of action under this theory requires more than simply stating that the defendant who invoked the power of sale was not the true beneficiary under the deed of trust. Rather, a plaintiff asserting this theory must allege facts that show the defendant who invoked the power of sale was not the true beneficiary. (See Herrera v. Federal National Mortgage Assn. (2012) 205 Cal.App.4th 1495, 1506 [plaintiff failed to plead specific facts demonstrating the transfer of the note and deed of trust were invalid].)

C. Borrower’s Standing to Raise a Defect in an Assignment

One basis for claiming that a foreclosing party did not hold the deed of trust is that the assignment relied upon by that party was ineffective. When a borrower asserts an assignment was ineffective, a question often arises about the borrower’s standing to challenge the assignment of the loan (note and deed of trust)—an assignment to which the borrower is not a party. (E.g., Conlin v. Mortgage Electronic Registration Systems, Inc. (6th Cir. 2013) 714 F.3d 355, 361 [third party may only challenge an assignment if that challenge would render the assignment absolutely invalid or ineffective, or void]; Culhane v. Aurora Loan Services of Nebraska (1st Cir. 2013) 708 F.3d 282, 291 [under Massachusetts law, mortgagor has standing to challenge a mortgage assignment as invalid, ineffective or void]; Gilbert v. Chase Home Finance, LLC (E.D.Cal., May 28, 2013, No. 1:13-CV-265 AWI SKO) 2013 WL 2318890.)[13]

California’s version of the principle concerning a third party’s ability to challenge an assignment has been stated in a secondary authority as follows:

“Where an assignment is merely voidable at the election of the assignor, third parties, and particularly the obligor, cannot … successfully challenge the validity or effectiveness of the transfer.” (7 Cal.Jur.3d (2012) Assignments, § 43.)

This statement implies that a borrower can challenge an assignment of his or her note and deed of trust if the defect asserted would void the assignment. (See Reinagel v. Deutsche Bank National Trust Co. (5th Cir. 2013) ___ F.3d ___ [2013 WL 3480207 at p. *3] [following majority rule that an obligor may raise any ground that renders the assignment void, rather than merely voidable].) We adopt this view of the law and turn to the question whether Glaski’s allegations have presented a theory under which the challenged assignments are void, not merely voidable.

We reject the view that a borrower’s challenge to an assignment must fail once it is determined that the borrower was not a party to, or third party beneficiary of, the assignment agreement. Cases adopting that position “paint with too broad a brush.” (Culhane v. Aurora Loan Services of Nebraska, supra, 708 F.3d at p. 290.) Instead, courts should proceed to the question whether the assignment was void.

D. Voidness of a Post-Closing Date Transfers to a Securitized Trust

Here, the SAC includes a broad allegation that the WaMu Securitized Trust “did not have standing to foreclosure on the … Property, as Defendants cannot provide the entire chain of title of the note and the [deed of trust].”[14]

More specifically, the SAC identifies two possible chains of title under which Bank of America, as trustee for the WaMu Securitized Trust, could claim to be the holder of the Glaski deed of trust and alleges that each possible chain of title suffers from the same defect—a transfer that occurred after the closing date of the trust.

First, Glaski addresses the possibility that (1) Bank of America’s chain of title is based on its status as successor trustee for the WaMu Securitized Trust and (2) the Glaski deed of trust became part of the WaMu Securitized Trust’s property when the securitized trust was created in 2005. The SAC alleges that WaMu did not transfer Glaski’s note and deed of trust into the WaMu Securitized Trust prior to the closing date established by the pooling and servicing agreement. If WaMu’s attempted transfer was void, then Bank of America could not claim to be the holder of the Glaski deed of trust simply by virtue of being the successor trustee of the WaMu Securitized Trust.

Second, Glaski addresses the possibility that Bank of America acquired Glaski’s deed of trust from JP Morgan, which may have acquired it from the FDIC. Glaski contends this alternate chain of title also is defective because JP Morgan’s attempt to transfer the Glaski deed of trust to Bank of America, as trustee for the WaMu Securitized Trust, occurred after the trust’s closing date. Glaski specifically alleges JP Morgan’s attempted assignment of the deed of trust to the WaMu Securitized Trust in June 2009 occurred long after the WaMu Securitized Trust closed (i.e., 90 days after December 21, 2005).

Based on these allegations, we will address whether a post-closing date transfer into a securitized trust is the type of defect that would render the transfer void. Other allegations relevant to this inquiry are that the WaMu Securitized Trust (1) was formed in 2005 under New York law and (2) was subject to the requirements imposed on REMIC trusts (entities that do not pay federal income tax) by the Internal Revenue Code.

The allegation that the WaMu Securitized Trust was formed under New York law supports the conclusion that New York law governs the operation of the trust. New York Estates, Powers & Trusts Law section 7-2.4, provides: “If the trust is expressed in an instrument creating the estate of the trustee, every sale, conveyance or other act of the trustee in contravention of the trust, except as authorized by this article and by any other provision of law, is void.”[15]

Because the WaMu Securitized Trust was created by the pooling and servicing agreement and that agreement establishes a closing date after which the trust may no longer accept loans, this statutory provision provides a legal basis for concluding that the trustee’s attempt to accept a loan after the closing date would be void as an act in contravention of the trust document.

We are aware that some courts have considered the role of New York law and rejected the post-closing date theory on the grounds that the New York statute is not interpreted literally, but treats acts in contravention of the trust instrument as merely voidable. (Calderon v. Bank of America, N.A. (W.D.Tex., Apr. 23, 2013, No. SA:12-CV-00121-DAE) ___ F.Supp.2d ___, [2013 WL 1741951 at p. *12] [transfer of plaintiffs’ note, if it violated PSA, would merely be voidable and therefore plaintiffs do not have standing to challenge it]; Bank of America National Association v. Bassman FBT, L.L.C. (Ill.Ct.App. 2012) 981 N.E.2d 1, 8 [following cases that treat ultra vires acts as merely voidable].)

Despite the foregoing cases, we will join those courts that have read the New York statute literally. We recognize that a literal reading and application of the statute may not always be appropriate because, in some contexts, a literal reading might defeat the statutory purpose by harming, rather than protecting, the beneficiaries of the trust. In this case, however, we believe applying the statute to void the attempted transfer is justified because it protects the beneficiaries of the WaMu Securitized Trust from the potential adverse tax consequence of the trust losing its status as a REMIC trust under the Internal Revenue Code. Because the literal interpretation furthers the statutory purpose, we join the position stated by a New York court approximately two months ago: “Under New York Trust Law, every sale, conveyance or other act of the trustee in contravention of the trust is void. EPTL § 7-2.4. Therefore, the acceptance of the note and mortgage by the trustee after the date the trust closed, would be void.” (Wells Fargo Bank, N.A. v. Erobobo (Apr. 29, 2013) 39 Misc.3d 1220(A), 2013 WL 1831799, slip opn. p. 8; see Levitin & Twomey, Mortgage Servicing, supra, 28 Yale J. on Reg. at p. 14, fn. 35 [under New York law, any transfer to the trust in contravention of the trust documents is void].) Relying on Erobobo, a bankruptcy court recently concluded “that under New York law, assignment of the Saldivars’ Note after the start up day is void ab initio. As such, none of the Saldivars’ claims will be dismissed for lack of standing.” (In re Saldivar (Bankr.S.D.Tex., Jun. 5, 2013, No. 11-10689) 2013 WL 2452699, at p. *4.)

We conclude that Glaski’s factual allegations regarding post-closing date attempts to transfer his deed of trust into the WaMu Securitized Trust are sufficient to state a basis for concluding the attempted transfers were void. As a result, Glaski has a stated cognizable claim for wrongful foreclosure under the theory that the entity invoking the power of sale (i.e., Bank of America in its capacity as trustee for the WaMu Securitized Trust) was not the holder of the Glaski deed of trust.[16]

We are aware that that some federal district courts sitting in California have rejected the post-closing date theory of invalidity on the grounds that the borrower does not have standing to challenge an assignment between two other parties. (Aniel v. GMAC Mortgage, LLC (N.D.Cal., Nov. 2, 2012, No. C 12-04201 SBA) 2012 WL 5389706 [joining courts that held borrowers lack standing to assert the loan transfer occurred outside the temporal bounds prescribed by the pooling and servicing agreement]; Almutarreb v. Bank of New York Trust Co., N.A. (N.D.Cal., Sept. 24, 2012, No. C 12-3061 EMC) 2012 WL 4371410.) These cases are not persuasive because they do not address the principle that a borrower may challenge an assignment that is void and they do not apply New York trust law to the operation of the securitized trusts in question.

E. Application of Gomes

The next question we address is whether Glaski’s wrongful foreclosure claim is precluded by the principles set forth in Gomes, supra, 192 Cal.App.4th 1149, a case relied upon by the trial court in sustaining the demurrer. Gomes was a pre-foreclosure action brought by a borrower against the lender, trustee under a deed and trust, and MERS, a national electronic registry that tracks the transfer of ownership interests and servicing rights in mortgage loans in the secondary mortgage market. (Id. at p. 1151.) The subject trust deed identified MERS as a nominee for the lender and that MERS is the beneficiary under the trust deed. After initiation of a nonjudicial forclosure, borrower sued for wrongful initiation of foreclosure, alleging that the current owner of the note did not authorize MERS, the nominee, to proceed with the foreclosure. The appellate court held that California’s nonjudicial foreclosure system, outlined in Civil Code sections 2924 through 2924k, is a “`comprehensive framework for the regulation of a nonjudicial foreclosure sale'” that did not allow for a challenge to the authority of the person initiating the foreclosure. (Gomes, supra, at p. 1154.)

In Naranjo v. SBMC Mortgage (S.D.Cal., Jul. 24, 2012, No. 11-CV-2229-L(WVG)) 2012 WL 3030370 (Naranjo), the district court addressed the scope of Gomes, stating:

“In Gomes, the California Court of Appeal held that a plaintiff does not have a right to bring an action to determine the nominee’s authorization to proceed with a nonjudicial foreclosure on behalf of a noteholder. [Citation.] The nominee in Gomes was MERS. [Citation.] Here, Plaintiff is not seeking such a determination. The role of the nominee is not central to this action as it was in Gomes. Rather, Plaintiff alleges that the transfer of rights to the WAMU Trust is improper, thus Defendants consequently lack the legal right to either collect on the debt or enforce the underlying security interest.” (Naranjo, supra, 2012 WL 3030370, at p. *3.)

Thus, the court in Naranjo did not interpret Gomes as barring a claim that was essentially the same as the post-closing date claim Glaski is asserting in this case.

Furthermore, the limited nature of the holding in Gomes is demonstrated by the Gomes court’s discussion of three federal cases relied upon by Mr. Gomes. The court stated that the federal cases were not on point because none recognized a cause of action requiring the noteholder’s nominee to prove its authority to initiate a foreclosure proceeding. (Gomes, supra, 192 Cal.App.4th at p. 1155.) The Gomes court described one of the federal cases by stating that “the plaintiff alleged wrongful foreclosure on the ground that assignments of the deed of trust had been improperly backdated, and thus the wrong party had initiated the foreclosure process. [Citaiton.] No such infirmity is alleged here.” (Ibid.; see Lester v. J.P. Morgan Chase Bank (N.D.Cal., Feb. 20, 2013) ___ F.Supp.2d ___, [2013 WL 633333, p. *7] [concluding Gomes did not preclude the plaintiff from challenging JP Morgan’s authority to foreclose].) The Gomes court also stated it was significant that in each of the three federal cases, “the plaintiff’s complaint identified a specific factual basis for alleging that the foreclosure was not initiated by the correct party.” (Gomes, supra, at p. 1156.)

The instant case is distinguishable from Gomes on at least two grounds. First, like Naranjo, Glaski has alleged that the entity claiming to be the noteholder was not the true owner of the note. In contrast, the principle set forth in Gomes concerns the authority of the noteholder’s nominee, MERS. Second, Glaski has alleged specific grounds for his theory that the foreclosure was not conducted at the direction of the correct party.

In view of the limiting statements included in the Gomes opinion, we do not interpret it as barring claims that challenge a foreclosure based on specific allegations that an attempt to transfer the deed of trust was void. Our interpretation, which allows borrowers to pursue questions regarding the chain of ownership, is compatible with Herrera v. Deutsche Bank National Trust Co., supra, 196 Cal.App.4th 1366. In that case, the court concluded that triable issues of material fact existed regarding alleged breaks in the chain of ownership of the deed of trust in question. (Id. at p. 1378.) Those triable issues existed because Deutsche Bank’s motion for summary judgment failed to establish it was the beneficiary under that deed of trust. (Ibid.)

F. Tender

Defendants contend that Glaski’s claims for wrongful foreclosure, cancellation of instruments and quiet title are defective because Glaski failed to allege that he made a valid and viable tender of payment of the indebtedness. (See Karlsen v. American Sav. & Loan Assn. (1971) 15 Cal.App.3d 112, 117 [“valid and viable tender of payment of the indebtedness owing is essential to an action to cancel a voidable sale under a deed of trust”].)

Glaski contends that he is not required to allege he tendered payment of the loan balance because (1) there are many exceptions to the tender rule, (2) defendants have offered no authority for the proposition that the absence of a tender bars a claim for damages,[17] and (3) the tender rule is a principle of equity and its application should not be decided against him at the pleading stage.

Tender is not required where the foreclosure sale is void, rather than voidable, such as when a plaintiff proves that the entity lacked the authority to foreclose on the property. (Lester v. J.P. Morgan Chase Bank, supra, ___ F.Supp.2d ___, [2013 WL 633333, p. *8]; 4 Miller & Starr, Cal. Real Estate (3d ed. 2003) Deeds of Trust, § 10:212, p. 686.)

Accordingly, we cannot uphold the demurrer to the wrongful foreclosure claim based on the absence of an allegation that Glaski tendered the amount due under his loan. Thus, we need not address the other exceptions to the tender requirement. (See e.g., Onofrio v. Rice (1997) 55 Cal.App.4th 413, 424 [tender may not be required where it would be inequitable to do so].)

G. Remedy of Setting Aside Trustee’s Sale

Defendants argue that the allegedly ineffective transfer to the WaMu Securitized Trust was a mistake that occurred outside the confines of the statutory nonjudicial foreclosure proceeding and, pursuant to Nguyen v. Calhoun (2003) 105 Cal.App.4th 428, 445, that mistake does not provide a basis for invalidating the trustee’s sale.

First, this argument does not negate the possibility that other types of relief, such as damages, are available to Glaski. (See generally, Annot., Recognition of Action for Damages for Wrongful Foreclosure—Types of Action, supra, 82 A.L.R.6th 43.)

Second, “where a plaintiff alleges that the entity lacked authority to foreclose on the property, the foreclosure sale would be void. [Citation.]” (Lester v. J.P. Morgan Chase Bank, supra, ___ F.Supp.2d ___, [2013 WL 633333, p. *8].)

Consequently, we conclude that Nguyen v. Calhoun, supra, 105 Cal.App.4th 428 does not deprive Glaski of the opportunity to prove the foreclosure sale was void based on a lack of authority.

H. Causes of Action Stated

Based on the foregoing, we conclude that Glaski’s fourth cause of action has stated a claim for wrongful foreclosure. It follows that Glaski also has stated claims for quiet title (third cause of action), declaratory relief (fifth cause of action), cancellation of instruments (eighth cause of action), and unfair business practices under Business and Professions Code section 17200 (ninth cause of action). (See Susilo v. Wells Fargo Bank, N.A. (C.D.Cal. 2011) 796 F.Supp.2d 1177, 1196 [plaintiff’s wrongful foreclosure claims served as predicate violations for her UCL claim].)

IV. JUDICIAL NOTICE

A. Glaski’s Request for Judicial Notice

When Glaski filed his opening brief, he also filed a request for judicial notice of (1) a Consent Judgment entered on April 4, 2012, by the United States District Court of the District of Columbia in United States v. Bank of America Corp. (D.D.C. No. 12-CV-00361); (2) the Settlement Term Sheet attached to the Consent Judgment; and (3) the federal and state release documents attached to the Consent Judgment as Exhibits F and G.

Defendants opposed the request for judicial notice on the ground that the request violated the requirements in California Rules of Court, rule 8.252 because it was not filed with a separate proposed order, did not state why the matter to be noticed was relevant to the appeal, and did not state whether the matters were submitted to the trial court and, if so, whether that court took judicial notice of the matters.

The documents included in Glaski’s request for judicial notice may provide background information and insight into robo-signing[18] and other problems that the lending industry has had with the procedures used to foreclose on defaulted mortgages. However, these documents do not directly affect whether the allegations in the SAC are sufficient to state a cause of action. Therefore, we deny Glaski’s request for judicial notice.

B. Defendants’ Request for Judicial Notice of Assignment

The “ASSIGNMENT OF DEED OF TRUST” recorded on December 9, 2008, that stated JP Morgan transferred and assigned all beneficial interest under the Glaski deed of trust to “LaSalle Bank NA as trustee for WaMu [Securitized Trust]” together with the note described in and secured by the Glaski deed of trust was not attached to the SAC as an exhibit. That document is part of the appellate record because the respondents’ appendix includes a copy of defendants’ request for judicial notice that was filed in June 2011 to support a motion for judgment on the pleadings.

In ruling on defendants’ request for judicial notice, the trial court stated that it could only take judicial notice that certain documents in the request, including the assignment of deed of trust, had been recorded, but it could not take judicial notice of factual matters stated in those documents. This ruling is correct and unchallenged on appeal. Therefore, like the trial court, we will take judicial notice of the existence and recordation of the December 2008 assignment, but we “do not take notice of the truth of matters stated therein.” (Herrera v. Deutsche Bank National Trust Co., supra, 196 Cal.App.4th at p. 1375.) As a result, the assignment of deed of trust does not establish that JP Morgan was, in fact, the holder of the beneficial interest in the Glaski deed of trust that the assignment states was transferred to LaSalle Bank. Similarly, it does not establish that LaSalle Bank in fact became the owner or holder of that beneficial interest.

Because the document does not establish these facts for purposes of this demurrer, it does not cure either of the breaks in the two alternate chains of ownership challenged in the SAC. Therefore, the December 2008 assignment does not provide a basis for sustaining the demurrer.

DISPOSITION

The judgment of dismissal is reversed. The trial court is directed to vacate its order sustaining the general demurrer and to enter a new order overruling that demurrer as to the third, fourth, fifth, eighth and ninth causes of action.

Glaski’s request for judicial notice filed on September 25, 2012, is denied.

Glaski shall recover his costs on appeal.

Wiseman, Acting P.J. and Kane, J., concurs.

ORDER GRANTING REQUEST FOR PUBLICATION

As the nonpublished opinion filed on July 31, 2013, in the above entitled matter hereby meets the standards for publication specified in the California Rules of Court, rule 8.1105(c), it is ordered that the opinion be certified for publication in the Official Reports.

KANE, J., concur.

[1] Mortgage-backed securities are created through a complex process known as “securization.” (See Levitin & Twomey, Mortgage Servicing (2011) 28 Yale J. on Reg. 1, 13 [“a mortgage securitization transaction is extremely complex”].) In simplified terms, “securitization” is the process where (1) many loans are bundled together and transferred to a passive entity, such as a trust, and (2) the trust holds the loans and issues investment securities that are repaid from the mortgage payments made on the loans. (Oppenheim & Trask-Rahn, Deconstructing the Black Magic of Securitized Trusts: How the Mortgage-Backed Securitization Process is Hurting the Banking Industry’s Ability to Foreclose and Proving the Best Offense for a Foreclosure Defense (2012) 41 Stetson L.Rev. 745, 753-754 (hereinafter, Deconstructing Securitized Trusts).) Hence, the securities issued by the trust are “mortgage-backed.” For purposes of this opinion, we will refer to such a trust as a “securitized trust.”

[2] Civil Code section 2924, subdivision (a)(1) states that a “trustee, mortgagee, or beneficiary, or any of their authorized agents” may initiate the nonjudicial foreclosure process. This statute and the provision of the Glaski deed of trust are the basis for Glaski’s position that the nonjudicial foreclosure in this case was wrongful—namely, that the power of sale in the Glaski deed of trust was invoked by an entity that was not the true beneficiary.

[3] Glaski’s pleading does not allege that LaSalle Bank was the original trustee when the WaMu Securitized Trust was formed in late 2005, but filings with the Securities and Exchange Commission identify LaSalle Bank as the original trustee. We provide this information for background purposes only and it plays no role in our decision in this appeal.

[4] Another possibility, which was acknowledged by both sides at oral argument, is that the true holder of the note and deed of trust cannot be determined at this stage of the proceedings. This lack of certainty regarding who holds the deed of trust is not uncommon when a securitized trust is involved. (See Mortgage and Asset Backed Securities Litigation Handbook (2012) § 5:114 [often difficult for securitized trust to prove ownership by showing a chain of assignments of the loan from the originating lender].)

[5] It appears this company is no longer a separate entity. The certificate of interested entities filed with the respondents’ brief refers to “JPMorgan Chase Bank, N.A. as successor by merger to Chase Home Finance, LLC.”

[6] One controversy presented by this appeal is whether this court should consider the December 9, 2008, assignment of deed of trust, which is not an exhibit to the SAC. Because the trial court took judicial notice of the existence and recordation of the assignment earlier in the litigation, we too will consider the assignment, but will not presume the matters stated therein are true. (See pt. IV.B, post.) For instance, we will not assume that JP Morgan actually held any interests that it could assign to LaSalle Bank. (See Herrera v. Deutsche Bank National Trust Co. (2011) 196 Cal.App.4th 1366, 1375 [taking judicial notice of a recorded assignment does not establish assignee’s ownership of deed of trust].)

[7] Specifically, the notice stated that his August 2008 installment payment and all subsequent installment payments had not been made.

[8] The signature block at the end of the NOD indicated it was signed by Colleen Irby as assistant secretary for California Reconveyance. The first page of the notice stated that recording was requested by California Reconveyance. Affidavits of mailing attached to the SAC stated that the declarant mailed copies of the notice of default to Glaski at his home address and to Bank of America, care of Custom Recording Solutions, at an address in Santa Ana, California. The affidavits of mailing are the earliest documents in the appellate record indicating that Bank of America had any involvement with Glaski’s loan.

[9] Bank of America took over La Salle Bank by merger in 2007.

[10] The trial court did not explicitly rule on defendants’ request for judicial notice of these documents, but referred to matters set forth in these documents in its ruling. Therefore, for purposes of this appeal, we will infer that the trial court granted the request.

[11] The claim that a foreclosure was conducted by or at the direction of a nonholder of mortgage rights often arises where the mortgage has been securitized. (Buchwalter, Cause of Action in Tort for Wrongful Foreclosure of Residential Mortgage, 52 Causes of Action Second (2012) 119, 149 [§ 11 addresses foreclosure by a nonholder of mortgage rights].)

[12] This allegation comports with the following view of pooling and servicing agreements and the federal tax code provisions applicable to REMIC trusts. “Once the bundled mortgages are given to a depositor, the [pooling and servicing agreement] and IRS tax code provisions require that the mortgages be transferred to the trust within a certain time frame, usually ninety dates from the date the trust is created. After such time, the trust closes and any subsequent transfers are invalid. The reason for this is purely economic for the trust. If the mortgages are properly transferred within the ninety-day open period, and then the trust properly closes, the trust is allowed to maintain REMIC tax status.” (Deconstructing Securitized Trusts, supra, 41 Stetson L.Rev. at pp. 757-758.)

[13] “Although we may not rely on unpublished California cases, the California Rules of Court do not prohibit citation to unpublished federal cases, which may properly be cited as persuasive, although not binding, authority.” (Landmark Screens, LLC v. Morgan, Lewis & Bockius, LLP (2010) 183 Cal.App.4th 238, 251, fn. 6, citing Cal. Rules of Court, rule 8.1115.)

[14] Although this allegation and the remainder of the SAC do not explicitly identify the trustee of the WaMu Securitized Trust as the entity that invoked the power of sale, it is reasonable to interpret the allegation in this manner. Such an interpretation is consistent with the position taken by Glaski’s attorney at the hearing on the demurrer, where she argued that the WaMu Securitized Trust did not obtain Glaski’s loan and thus was precluded from proceeding with the foreclosure.

[15] The statutory purpose is “to protect trust beneficiaries from unauthorized actions by the trustee.” (Turano, Practice Commentaries, McKinney’s Consolidated Laws of New York, Book 17B, EPTL § 7-2.4.)

[16] Because Glaski has stated a claim for relief in his wrongful foreclosure action, we need not address his alternate theory that the foreclosure was void because it was implemented by forged documents. (Genesis Environmental Services v. San Joaquin Valley Unified Air Pollution Control Dist. (2003) 113 Cal.App.4th 597, 603 [appellate inquiry ends and reversal is required once court determines a cause of action was stated under any legal theory].) We note, however, that California law provides that ratification generally is an affirmative defense and must be specially pleaded by the party asserting it. (See Reina v. Erassarret (1949) 90 Cal.App.2d 418, 424 [ratification is an affirmative defense and the defendant ordinarily bears the burden of proof]; 49A Cal.Jur.3d (2010) Pleading, § 186, p. 319 [defenses that must be specially pleaded include waiver, estoppel and ratification].) Also, “[w]hether there has been ratification of a forged signature is ordinarily a question of fact.” (Common Wealth Ins. Systems, Inc. v. Kersten (1974) 40 Cal.App.3d 1014, 1026; see Brock v. Yale Mortg. Corp. (Ga. 2010) 700 S.E.2d 583, 588 [ratification may be expressed or implied from acts of principal and “is usually a fact question for the jury”; wife had forged husband’s signature on quitclaim deed].)

[17] See generally, Annotation, Recognition of Action for Damages for Wrongful Foreclosure—Types of Action (2013) 82 A.L.R.6th 43 (claims that a foreclosure is “wrongful” can be tort-based, statute-based, and contract-based).

[18] Claims of misrepresentation or fraud related to robo-signing of foreclosure documents is addressed in Buchwalter, Cause of Action in Tort for Wrongful Foreclosure of Residential Mortgage, 52 Causes of Action Second, supra, at pages 147 to 149.